Apart from necessary women or housekeepers, the UK government did not employ any women until 1869 when it acquired the nascent inland telegraph industry and with it a number of female telegraphists who became employees of the General Post Office and hence civil servants. The Postmaster General, who realised that he had acquired a source of very capable workers who did not need to be paid anything like as much as their male counterparts, next year introduced women clerks elsewhere in his organisation. He summarised his reasons as follows:

- They have in an eminent degree a quickness of eye and ear and a delicacy of touch, which are essential qualifications of a good operator.

- They take more kindly than men or boys to sedentary employment and are more patient during long confinement to one place.

- The wages offered will attract male operators from an inferior class of the community and will attract females from a superior class.

- The superior class women will write and spell better than the inferior men, and where the staff is mixed will raise the tone of the whole staff.

- Women are less disposed to get together to extort higher wages.

- Women will not require increases related to length of service as they will retire for the purpose of getting married as soon as they get the chance. (He left this decision of retiring on marriage to the women and their husbands having remarked ”we do not punish marriage by dismissal” (p147, Martindale).

- There will also be fewer women than men on the pension list.

The women were paid 14 shillings (70 pence) a week; considerably less than their male counterparts. There was uproar from the male clerks who complained about the “grievous dangers, moral and unofficial, which are likely to follow the adoption of so extraordinary a course”, but the ceiling had been broken.

Jeanie Senior was the first woman to be appointed as a civil servant outside the Post Office when she was in 1873 appointed as the first female inspector of the education of girls in pauper schools and workhouses.

The Playfair Commission of 1874-5 concluded that "women are well qualified for clerical work of a less important character and are satisfied with a lower rate of pay than is expected by men similarly employed. We, therefore see no reason why the employment of female clerks should not be extended to other departments where the circumstances will admit of it. In the Telegraph Office, male and female clerks are employed in the same rooms without inconvenience. But, as regards the ordinary clerical work of an office, we are not prepared to recommend the employment of women unless they can be placed in separate rooms, under proper female supervision."

In 1875 forty ‘young ladies’ were taken on in the newly created Daily Balance section of the Savings Bank, which was part of the General Post Office. This was seen by some, including its Controller, as ‘the agreeable fad of a few influential people’ because it was clearly beyond the capacity of women to add and subtract figures and anything like a balance sheet would be outside women’s comprehension. The Controller later recalled his surprise that the pretty girls were taking the work seriously and adding up figures without making mistakes. The Post Office Journal printed objections to the women working, which included the vigorous protest of the Controller, who with his staff points out that there are grievous dangers both moral and official in employing women. The gentlemen of the office even contemplated holding an ‘indignation’ meeting in protest. One clerk, giving evidence to the Playfair Commission, stated that some women would be able to do some of the lighter office work, but that they would be unable to wield the ‘heavy pressure, using very hard pens and carbon paper required for the job.

A Miss M.C. Smith entered the GPO in 1875. A few months later it was decided to increase the number of women employed and to put them under the supervision of a woman. Although only 23 years old, Miss Smith was given the post of Lady Superintendent and put in charge of 64 women. After an investigation into the work of the women’s division, the report to the Postmaster-General said that ‘women’s division was admirably managed and that the work was both well done and economical’. Although women had been seen as ‘unpromising’ it was Miss Smith’s demonstration of organising and training that demonstrated that women could do well in clerical duties. She was instrumental in enabling women to extend the variety of work they were allowed to undertake. Indeed she is said to ‘never turn an opportunity for women down’. Henry Fawcett was appointed Postmaster-General in 1880 and abolished the requirement that women needed to be recommended for work in the Post Office. They would instead enter open competitions, which were already the post-Northcote-Trevelyan recruitment route for men. By 1896 the female staff in the GPO, under Miss Smith had grown to 900.

These and other developments meant that it became acceptable for unmarried middle class women to undertake paid work. Women were, in the following years, appointed to posts in the Registrar General's Office, the Inland Revenue, the Local Government Board, the Board of Education, the National Health Insurance Commission and the Board of Trade.

Typewriters

In a sign of what was to come, many women were employed as typewriters - i.e. they operated what we would today refer to as a typewriter. Sir Algernon Edward West told how he was a very quick writer, although his writing was illegible. He said that “these ‘typewriting women’ can beat me two to one in writing and that shows the amount of work we can get from them”. But the one lady typewriter in the Department of Agriculture was confined to a room in the basement and the chief clerk issued instructions that no member of staff over the age of 15 was to enter her room. Another department locked their female typewriters in their room, serving their meals through a hatch in the wall. The first two women were employed in the place of three men copyists and they turned out the work of four copyists. As their numbers grew they were marched crocodile style by the superintendent to collect their pay.

Inspectors

The Chief Inspector of Factories, in his annual report of 1879 said “I doubt very much whether the office of factory inspector is one suitable for women” and that "the duties of a factory inspector would be incompatible with the gentle, home-loving character of a woman". However, Home Secretary (later to be Prime Minister) H H Asquith appointed the first two women inspectors - both experienced in their field - to improve the working conditions for women working in factories, sweatshops and cottage industries.

In England the women were segregated both physically and appointed to deal only with women’s trades. They worked under their own woman head. In Scotland, a radically different arrangement was instituted. The country was split into six districts and one of those districts was given a woman inspector in charge of both men and women. This was the first experiment of aggregation in the civil service, where men and women worked side by side. In 1914 the numbers of women inspectors in the civil service, was given as 200, with 18 in the ‘Factory Department of the Home Office’. These women would have specialised in the working conditions in factories employing women and children.

Hilda Martindale joined the Home Office in 1907 as a factory inspector. She rose to the rank of Deputy Chief Inspector and campaigned for the removal of the marriage bar.

Royal Commission on the Civil Service &

The McDonnell Commission

The Royal Commission of 1912 looked into the conditions under which women should be employed in the civil service. They took as their guiding principle that “the object should be not to provide employment for women as such, but to secure for the State the advantage of the services of women whenever those services will best promote its interests”. They did not accept, however, that “differences of sex should be ignored in recruiting for service”. They also stated that “the responsibilities of married life are normally in-compatible with the devotion of a woman’s whole-time and unimpaired energy to the Public Services” and that the salaries of “women should be fixed on a lower scale than those of men”. They also stated that ”female clerks, where employed should be accommodated separately from male clerks”, although later they said that in particular cases such objections, based on segregation, should not be a decisive reason not to employ women in the same branch of service.

But there were significant reservations in the report and differences of opinion were around how women were recruited and their salaries. The majority recommended open recruitment of women by separate examination, with a minority suggesting that there should be a limited number of places for women using the Class 1 examination. As for salary, a majority thought that there should be a Treasury enquiry into removing the inequalities of salary and that women should be paid the same as men for the same work. The minority opinion was a “scale adequate for men was excessive for women” because, after all, women did not have families to keep. There was also a minority opinion which favoured the extension of the employment of women into the upper ranks of the Service, but to a lesser extent than the lower ranks.

Similar issues were debated by the 1914 McDonnell Commission who in particular questioned the need for the marriage bar, arguing that it might act as a deterrent to marriage with a consequential "loss to the Nation of mothers of a specially selected class".

World War I

As in so many other areas, the 1914-18 First World War catalysed significant change in the employment of women in the civil service. A large number of women were recruited to release men to join the army so that the number of women in the civil service increased five-fold to approaching 200,000, over 50% of the total. Some were given real responsibility but most were employed as clerks and typists.

The arrival of the new temporary women clerks was not greeted with unalloyed joy by the existing staff. In the July 1915 edition of Red Tape, the publication of the Assistant Clerks’ Association, one correspondent suggested that it had not been demonstrated that ‘the supply of unemployed men clerks whose services could have been obtained for a reasonable wage, had been exhausted.’ The second, and possibly more serious concern expressed, was that there had been ‘a good deal of petty patronage in introducing temporary women clerks into the Civil Service.’ For Assistant Clerks, who had been obliged to undergo stringent examinations in a range of subjects to obtain their posts, this was anathema. It appeared to be a return to the system which existed before the reform of recruitment practices arising from the Northcote-Trevelyan Report (1854) and, as a result, it aroused a great deal of suspicion.

The arrival of the new temporary women clerks was not greeted with unalloyed joy by the existing staff. In the July 1915 edition of Red Tape, the publication of the Assistant Clerks’ Association, one correspondent suggested that it had not been demonstrated that ‘the supply of unemployed men clerks whose services could have been obtained for a reasonable wage, had been exhausted.’ The second, and possibly more serious concern expressed, was that there had been ‘a good deal of petty patronage in introducing temporary women clerks into the Civil Service.’ For Assistant Clerks, who had been obliged to undergo stringent examinations in a range of subjects to obtain their posts, this was anathema. It appeared to be a return to the system which existed before the reform of recruitment practices arising from the Northcote-Trevelyan Report (1854) and, as a result, it aroused a great deal of suspicion.

The new arrivals were not particularly welcomed by the permanent female staff either. One criticised the “temporary”, who came ‘in all the glory of paint and powder, short skirts, high cloth boots, transparent blouses. She came – men saw – she conquered…. I have heard tell of men, formerly confirmed misogynists, who now sit surrounded by a bevy of beauty and find the official day all too short.’

Then, after the end of the war, decisions had to be made about the distribution of peacetime jobs. A Women’s Advisory Committee was accordingly appointed in 1918 to advise the Minister for Reconstruction. Links to the committee's report are at the bottom of this webpage.

The committee accepted that returning heroes must have their fair share of the jobs, but argued that it would be foolish to turn the clock back and lose capable workers simply on the grounds of sex. It would be an even greater folly, they thought, to send away those women who had demonstrated 'administrative capacity of high grade' during the war. In the short term, therefore, women who had proved their worth should be eligible for appointment to government posts. In the long term, all civil service jobs should be opened to women on the same terms as to men.

Post-War Legislation

But the Government were not persuaded and limited its acknowledgment of the contribution of women to the war effort to the two pieces of legislation.

The first was The Representation of the People Act 1918 (‘The Fourth Reform Act’). This greatly increased the numbers of those entitled to vote by abolishing practically all property qualifications for men and by enfranchising women over 30 who met minimum property qualifications. Women over 30 years old received the vote if they were either a member, or married to a member, of the Local Government Register, a property owner, or a graduate voting in a University Constituency. Full electoral equality for women did not occur until the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928.

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 then enabled women to enter the legal profession and the civil service and to become jurors. In a broad opening statement it specified that “A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation”. This Act accordingly provided employment opportunities for individual women, and many were appointed as magistrates, but in practice it fell far short of the expectations of the women’s movement, for it was all too often argued that women were not suited for appointment to particular positions or occupations. Senior positions in the civil service remained closed to women (other than on promotion) and they could be excluded from juries if evidence was likely to be too “sensitive”. Coupled with hostile attitudes to their employment at a time of economic crisis, this placed obstacles in the way of women and reduced the effectiveness of the legislation.

Further Developments

The next significant advance occurred in 1925 when women could now be recruited (e.g. direct from university) into the Administrative Class (i.e. the higher policy-making reaches) of the Home Civil Service. A small number of women had previously been promoted into that class from the executive grades.

Nothing much then changed until the publication in 1931 of report of the Royal Commission on the Civil Service (The Tomlin Report). The Commission found that the Home Civil Service had tested the get-out clause on the 1919 legislation to the limit. Despite the 1925 breakthrough, there were only 13 women Assistant Principals, 6 women Principals, 2 women Assistant Secretaries, and no women above this level. Most departments employed no women in responsible posts, whilst the Ministry of Defence, for instance, employed no women other than typists, and the Post Office channeled all female employees into a separate, more poorly paid, Women's Branch. It had remained inconceivable, it seemed, that a male employee might be expected to take orders from a female superior.

The Tomlin Report seems to have opened a few more doors. Audrey J Lenfestey, for instance, was in 1934 the first woman to take and pass an entrance exam and interview for appointment as a cadet intelligence officer in the Department of Overseas Trade. Her salary scale ran from £215 to £301. The appointment was newsworthy enough to be the subject of a story in the Daily Mail which noted that she had scored 250 out of a maximum of 300 in 'the new "subject" of personality'. The Evening News tried to interview her but found her to be 'a very retiring young woman': ''I'm English" said Miss Lenfestey, demurely,. But beyond that she would not go.'

The number of Assistant Secretaries and above had nevertheless increased to only 13 by 1943. But Evelyn Sharp's promotion to Permanent Secretary in 1955 was a significant milestone. (She was, however, quoted as referring to the "unreliability of women", and their lesser financial responsibility when compared with men.)

The Marriage Bar

The main problem was undoubtedly the attitude of senior officials, but the Marriage Bar also deterred ambitious women from entering the civil service and/or ensured that, once recruited, they were forced to leave. The civil service was far from the only organisation to forbid their female staff - and indeed their male staff - to marry without the employer's permission. I do not know, but I suspect, that it was one of the last organisations to abolish such rules.

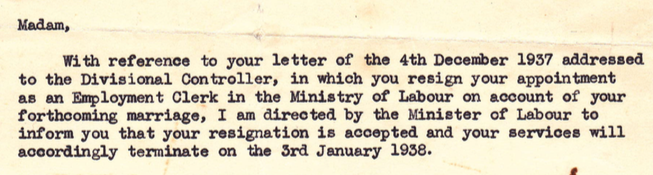

The marriage bar prohibited married women from joining the civil service, and required women civil servants to resign when they became married (unless granted a waiver). It was not abolished until October 1946 for the Home Civil Service and 1973 for the Foreign Service. A film by Alun Parry for the PCS union provides a revealing view of the frustration felt by many able women before the marriage bar was lifted.

I am very grateful to Sue Randall for sending me copies of two delicious letters to her grandmother, 33 year old Edith Mary Buckthorp, née Hollingworth, who married in 1938. The first (extract above) accepts her (forced) resignation. The second confirms her marriage gratuity. (The second letter also confirms return of Mrs Buckthorp's marriage certificate which she in fact never received, to her considerable and lasting annoyance.)

A younger Edith Hollingworth is in this photo of the female staff of the Bolton Ministry of Labour taken around 1929. (Employment Exchanges had separate entrances and separate staffing for men and women well into the 1960s.)

The photo probably records a works outing given the presence of the dog. Edith is in the front row in the striped top, with glasses. The older woman, back row, second from left, is Miss Laurie the "boss".

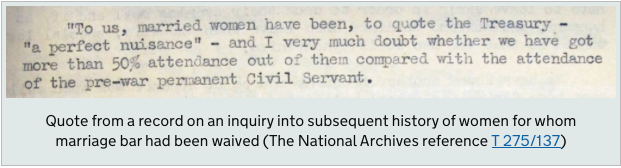

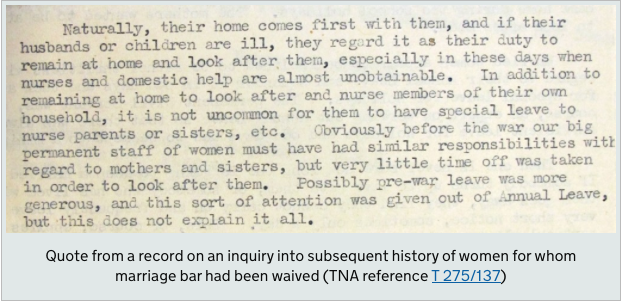

Here are two extracts from a 1947 inquiry following the abolition of the marriage bar. It seems that married women had turned out (to some at least) to be 'a perfect nuisance'.

Equal Pay?

The National Health Insurance Commission was created by Parliament in 1911 and was initially staffed by promising assistants from other government departments, including four women Insurance Commissioners. They were to receive equal pay with their male colleagues: one of the very first times women were given equal pay.

But the only female Inspector of Prisons was in 1913 paid only half the salary of her male colleagues.

The Government was defeated in a 1936 House of Commons vote, tabled by Ellen Wilkinson and supported by Lady Astor, suggesting that female civil servants doing the same work as males should receive the same pay. But Prime Minister Baldwin refused to be bound by the vote.

Women's Civil Service pay scales remained lower than those of men of the same grade until 1961, equal pay having been implemented in seven annual installments, beginning in 1955. And there were some promotion bars. In 1940, for instance, Margaret Rock could not be promoted to codebreaker at Bletchley Park. The BBC and the London County Council had implemented equal pay in 1942 - in the middle of World War II, but the Council of Women Civil Servants (see below) felt that it would be inappropriate for civil servants to press their claim for equal pay during the war.

See the Current Issues web-page for information and a discussion about the current gender pay gap.

The Council of Women Civil Servants was formed in 1920 to fight for women's causes. Their first triumph was the 1925 recruitment policy change mentioned above. They were however unable to persuade the 1933 Schuster Committee to recommend that women should be admitted to the Diplomatic Service. The Committee listed a number of reasons for their conclusion, including the unanimous opposition of the heads of Embassies etc. abroad (and their wives) and the supposed fact that many foreign countries would not wish to accept women as diplomats. And the final sentence of their report was: 'From the evidence submitted to us, it is by no means clear that the majority of British womanhood would wish to see this country represented abroad by women.' This bar, like the marriage bar in the Home Civil Service, was eventually lifted in 1946. The Council was wound up in 1958.

Dame Evelyn Sharp became the first woman Permanent Secretary in 1955, followed by Dame Mary Smieton in 1959.

The Times felt it worth reporting in September 1958 that two women were by then working in the Administrative Class whilst bringing up families, and 36 women in that class were married.

The 1971 Kemp-Jones report on The Employment of Women in the Civil Service made a number of recommendations aimed at improving the career prospects of women with family responsibilities. Maybe as a result of this, Ann Taylor thinks that she may have been amongst the first of the more senior women civil servants to be allowed to work part-time, beginning in 1979. She was employed by the Department of Trade and Industry.

The Sex Discrimination Act became law in 1975.

Prime Minister Tony Blair and Cabinet Secretary Gus O'Donnell launched a 10 Point Plan in November 2005 aimed at improving civil service diversity, followed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown who launched a diversity strategy in 2008 (Promoting Equality, Valuing Diversity). The consensus, however, seems to be that central initiatives are relatively ineffective, and those who work in line departments are well advised to 'get on and do their own thing'. (See for instance the 2015 IfG Report.)

For comparison purposes:

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was in 1873 the first woman to qualify as a doctor. The BMA thereupon voted not to admit any further women - a bar which lasted until 1892.

Mrs Edith Smith was the first woman to be sworn in (in Grantham in 1915) as a proper police officer with full powers of arrest. The Metropolitan Police followed in 1918 by appointing 25 women with limited powers of arrest, reporting to a Mrs Stanley as Superintendent. These 25 had previously been Voluntary Police Aides, and had no connection with the Suffragettes. Other volunteers, who had participated in the militant Suffragette movement were not allowed to join.

The first woman MP - i.e. elected to the British House of Commons - was Countess Constance de Markievicz (born Constance Gore-Booth) who was elected as the Sinn Féin MP for the Dublin St Patrick's constituency in 1918. She did not take up her seat and Dublin became the capital city of the newly independent Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) in 1922.

Nancy, Viscountess Astor was the first woman to take a seat in Parliament. Born in Virginia, she moved to England following her divorce from her first husband and subsequently married Waldorf Astor in 1906. In 1919 her husband, who was MP for Plymouth Sutton, succeeded to the peerage and she was elected in his stead for the Conservative party. She held the seat until she retired in June 1945.

The first woman British Government Minister, Labour's Margaret Bondfield, was appointed in 1924. She subsequently became the first woman Cabinet Minister in 1929 (see photo on right).

Baroness Wootton and Baroness Swanborough were in 1958 the first women to be entitled to sit in the House of Lords.

Shirley Williams was appointed as a junior minister in the Ministry of Labour in 1966, her appointment (according to her) having been opposed by the ministry's Permanent Secretary, Sir James Dunnett. Even worse, he then subsequently refused to to communicate directly with her on any matter. Civil servant Kate Jenkins also worked in a department headed by Sir James, and later reported that he had explicitly refused to promote any woman beyond the rank of Principal. (Kate subsequently had great difficulty persuading Parliamentary Counsel (and father of four) that pregnancy usually lasted 40, not 36 weeks, whilst working on maternity leave legislation.

Margaret Thatcher became the first female Prime Minister in 1979.

Baroness Young became the first female Leader of the House of Lords in 1981. She was the only woman ever appointed to the Cabinet by Margaret Thatcher.

Barbara Castle was the first woman to be appointed First Secretary of State (broadly equivalent to Deputy Prime Minister) in 1968.

And in Academia ...

Cambridge allowed women to sit exams from 1869, in the same year that Girton College was founded - the first college in England to educate women. But Cambridge did not formally admit women until 1948.

Women could sit Oxford University undergraduate-level exams, equivalent to those taken by men, from 1875 but they could not be formally admitted to the university, and so be awarded a formal university degree, until 1920. The first woman's college, Lady Margaret Hall, was founded in 1878. The first woman to gain honours in an Oxford 'Examination of Women' was Annie Rogers who in 1877 gained first class honours in Latin and Greek, despite not having been admitted to a college. She followed this with first class honours in Ancient History, and returned to Oxford to graduate 'properly' in 1920. Gertrude Bell gained a First in Modern History in 1878.

The University of London was in 1880 the first English university to award degrees to women - see photo below.

Further Reading

Bea Morgan has written a detailed history of women in the UK civil service.

Michael Coolican's No Tradesmen and No Women has some interesting and well written detail on both the early years of women in Whitehall and the glass ceiling that persists through to the present day.

The 1919 report of the Women's Advisory Committee ran to only eight pages. Click these links to see a photo of each page:-

Title page - Membership & Terms of Reference - Page 3 - Page 4 - Page 5 - Page 6 - Page 7 Recommendations - Page 8 Recommendations cont'd & Appendix

(It is interesting to note that committee members Lucy Streatfield and Rosalind Nash are referred to as appendages of their husbands - i.e. as 'Mrs Granville Streatfield' and 'Mrs Vaughan Nash' - in the formal list of members.)

Timely Assistance - The Work of the Society for Promoting the Training of Women 1859-200 - by Anne Bridger and Ellen Jordan contains numerous references to the civil service, and some delicious quotes.