Gertrude Bell was born on 14 July 1868 in Washington, County Durham, destined to become what many believe to have been the greatest woman of her time. Her family had risen over three generations from being Cumbrian sheep farmers to becoming innovative, successful (and hence very wealthy) colliers and ironmasters with progressive attitudes. (Her father’s company built the famous Transporter Bridge over the River Tees.)

Her family’s background and attitudes meant that Gertrude was adept at meeting all social classes on equal terms, whilst generally moving in well-connected circles. Her uncle, for instance, was later the British ambassador to Persia (now Iran). But Gertrude was never fully accepted by the aristocracy as her wealth derived from ‘trade’ rather than property and inheritance. Equally, she had no wish to join the aristocracy. When her grandfather was made a Baronet she commented that “he quite deserves it only I wish it could have been offered and refused”.

Childhood and Education

In the first of many tragedies and set-backs in her life, Gertrude’s mother died when she was 3. Her father remarried and he and his new wife had three children, so Gertrude, who already had one brother, became the eldest of five. She was very athletic, willful, adventurous, impetuous and brave, and so got into numerous scrapes as well as enjoying throwing her dog into a pond every day because ‘he does hate it so much’.

As she got older she also became obviously very clever as well as opinionated, and quick at light repartee, so she projected a sense of inner strength unmatched by other young women in her circle. Her biographer notes that she was often angered by the incomprehension of ‘normal’ people, and their inability to base their views on accepted facts and other evidence. These qualities, together with her aptitude for work, turned her into an outstanding pupil at Queen's College, Harley Street, London, a leading girls' school, and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, which she entered in April 1886. Equally, however, she was something of a social hand grenade. She was not yet eighteen, ‘half child, half woman, rather untidy’, though contemporaries were impressed by her athletic accomplishments—she could swim, fence, row, play tennis and hockey—as well as her breadth of reading and considerable self-confidence.

But Oxford, and wider society, remained very male dominated. Special applications had to be made for women to attend lectures and take exams. One contemporary philosopher wrote that ‘the over-taxing of [women’s] brains would lead to the deficiency of reproductive power’. Another tutor made the women in the room sit with their backs to him. But Gertrude, after only two years (not the normal three), became the first woman to win a first-class degree in modern history.

Returning to the family home in Redcar, she tutored her younger sisters and assisted her stepmother in philanthropic work among working people employed in the family's ironworks and collieries. Summers were at first spent attending the London social season, where she acquired a lifelong habit of cigarette smoking. She was an attractive young woman: slender and erect, with fine features, piercing greenish eyes, and a mass of thick light auburn hair usually assembled on the top of her head. Gertrude's attractiveness drew much from her vivacity, physical fitness, and constant, sometimes excessive, preoccupation with clothes. The round of balls and entertainments failed, however, to culminate in marriage.

Travels

After completing her studies, her family were determined to rid Gertrude of her ‘Oxfordy manner’ – for perhaps no-one would otherwise want to marry her. She accordingly embarked on a series of overseas journeys, punctuated by spells at home, or mountaineering, or supporting the anti-suffrage league. Indeed she spent most of the next 26 years (i.e. until she was 46) learning Arabic, Persian, French and German; and traveling throughout Europe and the Middle East.

Her journeys became more and more adventurous, especially in the way in which, from 1909, she travelled lands controlled by various Bedouin tribes, ruled by Sheiks whose women were virtually enslaved. She took huge risks but survived – and won their respect – by traveling in considerable style and at considerable expense, knowing that the sheikhs would judge her status by her possessions, her entourage and her gifts.

Mountaineering

She took up mountaineering in 1899, beginning with La Meije – see photo above - which she climbed in her underclothes as she owned no trousers and her skirt was too cumbersome. She went on to tackle increasingly dangerous ascents, and became known as the greatest woman mountaineer of her age. She nearly died in a storm in 1901 but carried on climbing until she climbed the Matterhorn around her 36th birthday in 1904. This mountain is portrayed in her memorial window in East Rounton Church, opposite a vignette of Gertrude on the back of a camel.

Anti-Suffrage League

It is very surprising, these days, to learn that Gertrude opposed the Suffragettes and indeed became honorary secretary of the British Women's Anti-Suffrage League. She thought that the suffragettes’ activities were tantamount to terrorism, and noted that only a quarter of men owned sufficient property to be entitled to vote. (The vote could not be confined to propertied women as the assets of married women automatically became that of their husband on marriage.) She also doubted that most women were yet educated enough or prepared in other ways to take part in deciding how a nation should be ruled. She accordingly argued that social and property issues should be tacked before turning to the question of the franchise.

The First World War

Like many middle class women, she volunteered to work during the war – the first time she had done so. She ran a significant Red Cross ‘Wounded and Missing Enquiry Department’ and proved to be a formidable administrator. “I think I have inherited a love of office work! A clerk was what I was meant to be.”

But her unique and invaluable knowledge of Arabia its people meant that she was asked to travel out to Cairo towards the end of 1915 in order to become the first ever woman officer in British Military Intelligence. She was not to everyone’s taste, therefore, ‘though one admirer told a colleague – on her subsequent move to Basra - that he should take her seriously as ‘She is a remarkably clever woman … with the brains of a man’.

Post-War

Once the Turks had been expelled from Mesopotamia, Gertrude was employed as Oriental Secretary in the post-conflict civil administration – this becoming a civil servant. In that role, she became pretty well indispensable, often working alongside T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), another Oxford modern history graduate. She was given an immense amount of power for a woman at the time. She has been described as "one of the few representatives of His Majesty's Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection".

Once the Turks had been expelled from Mesopotamia, Gertrude was employed as Oriental Secretary in the post-conflict civil administration – this becoming a civil servant. In that role, she became pretty well indispensable, often working alongside T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), another Oxford modern history graduate. She was given an immense amount of power for a woman at the time. She has been described as "one of the few representatives of His Majesty's Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection".

She was not too impressed by the machinations of British London-based politicians, and was particularly critical of the Sykes-Picot treaty and Lord Balfour’s Declaration:- “… if only people at home would not make pronouncements how much easier it would be for those on the spot”. She was a major driving force behind the creation of the Hashemite dynasties in what are now Jordan and Iraq , including through

- becoming a close confidant of (soon-to-be) King Faisal,

- playing a significant role in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference,

- writing what was later considered a 'masterful' 1920 official report, Self Determination in Mesopotamia.

- writing another very influential report – also in 1920 - entitled Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia;

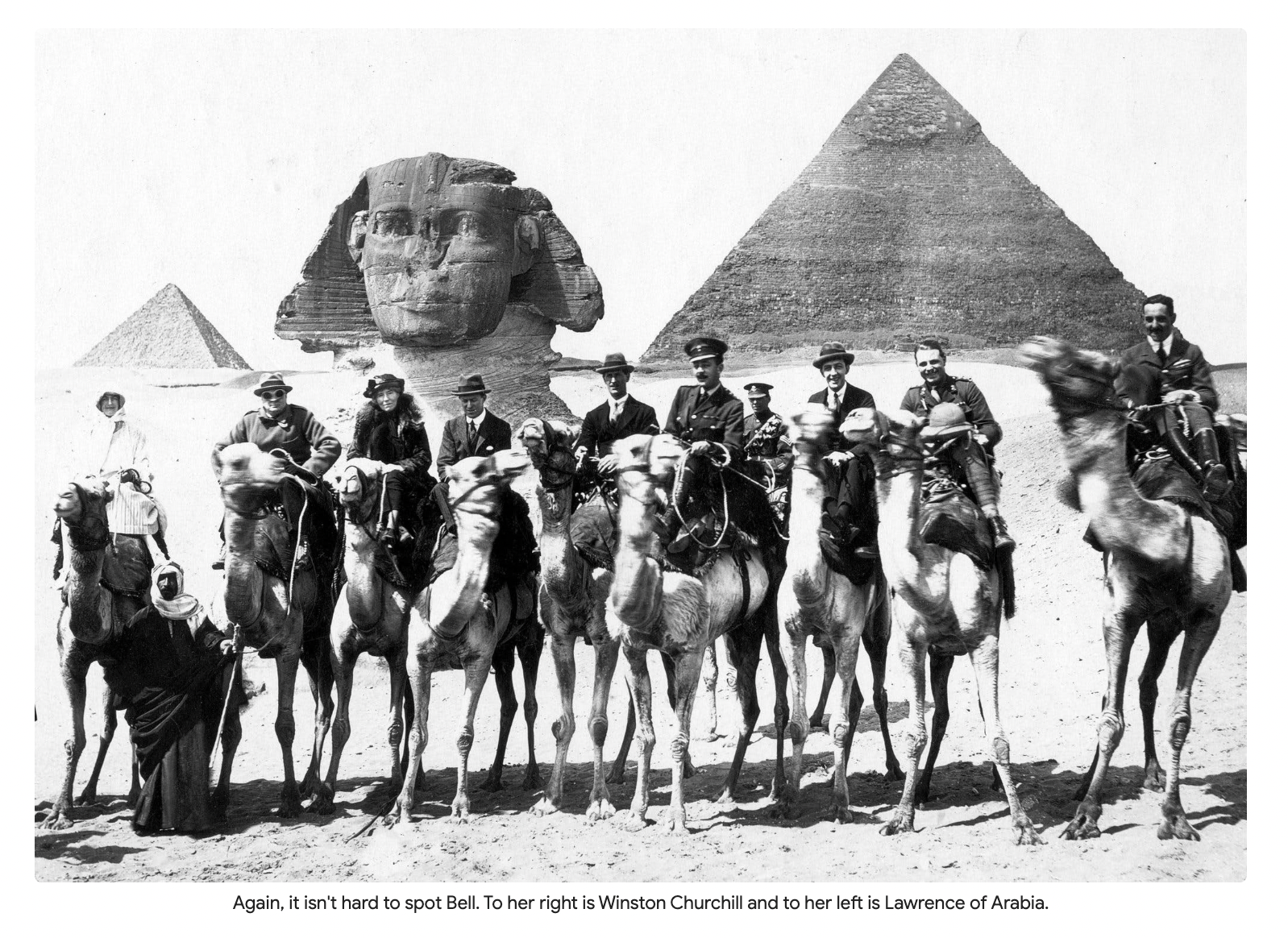

- playing a vital role at the 1921 Cairo conference convened by Winston Churchill (see photo below) to determine the boundaries of the British mandate and nascent states such as Iraq. (Among other things the protocol fixed Iraq's frontiers with Jordan and Saudi Arabia and, more importantly, with Turkey. It left unsolved, however, the question of the former Mosul vilayet with its Kurdish population.)

Personal Life

Gertrude fell in love, aged 24, with an impecunious official in the Teheran Legation called Henry Cadogan, and they announced their engagement. But Gertrude’s parents refused to give her permission to marry him, and he died of pneumonia around a year later. This was an episode in her life from which she would never fully recover.

She was unlucky again, some years later, when she fell deeply in love with the already (and slightly unhappily) married Major Dick Doughty-Wylie. He visited her (without his wife) in 1913 and she encouraged him to come to her bedroom, but she at the last minute refused to consummate the affair. Their subsequent relationship inevitably waxed and waned until she was devastated when he was killed at Gallipoli in 1915.

Then, in the early 1920s, she became infatuated with Ken Cornwallis, a British adviser to Iraq's Ministry of the Interior and King Faisal’s personal counselor. He was fond of her, but (at 15 years her junior) he was not interested in developing their relationship.

The 1920s (and her 50s) were therefore an increasingly difficult decade for Gertrude. Her work was now much less challenging. She had been politely but firmly rejected by Ken Cornwallis, and his attitude did not change even after his divorce in 1925. She was getting increasingly sharp tongued when dealing with those whom she did not respect, freezing one lunch party in Baghdad by asking, in front of a colleague’s young wife, “Why will promising young Englishmen marry such fools of women?”

Gertrude’s health also declined. She was hospitalized with pleurisy and it is possible that she had been told that she was suffering from lung cancer after many years of heavy smoking.

She found some consolation in archaeology, gathering funds for a national museum in Baghdad, which was inaugurated in 1923 and is still open today. She also tried to help the Muslim women in Baghdad, who were largely confined indoors; she organized tea parties for them and arranged a series of lectures from a woman doctor.

She received another blow when her half-brother Hugo died from typhoid in February 1926. On 12 July 1926, she was discovered dead of an apparent overdose of sleeping pills. It is not known whether she intended to take her own life or whether the overdose was accidental. What is certain, however, is that she left behind a reasonably benevolent, incorrupt and effective Iraq government. And the Iraqi Hashemite dynasty that she had helped put in place continued until 1958 – a happy contrast to what has happened since then under Saddam Hussein and others.

Much more detail is to be found in Georgina Howell’s brilliant and highly readable biography Queen of the Desert. I also strongly recommend James Barr's A Line in the Sand as a terrific history of the mainly disastrous interventions of the Western powers in the Middle East from the early days of the First World War through to the end of the Second World War - interventions which have serious repercussions right through to the present day.