Blockages

The Cabinet Office, assisted by the Hay Group, published an interesting report, Women in Whitehall, in 2014. It diagnosed significant challenges facing the Civil Service in removing the blockages preventing talented women from succeeding.

In particular, the report concluded that the culture and leadership climates were preventing talented women from progressing into more senior roles. When combined with current pay constraints this meant that the talent pool from which leaders could recruit was significantly smaller than it could be which, in turn, constrained performance. More positively, it found that women entering the SCS possess exactly the leadership capabilities required to progress into more senior roles and they have the ambition to be promoted in equal measure to men. The challenge therefore was how to create the conditions in which this talent can prosper.

Female Chaps?

The IfG in 2015 published an excellent report by Joe Devanny and Catherine Haddon looking at the history of women in the Senior Civil Service since 1945. Their final chapter drew some particularly interesting conclusions about the continuing need for senior women to be 'the right sort of chap' in both background and behaviour. Here are some extracts from the report:

"The academic Sophie Watson posed a series of questions about civil service culture in the period up to the mid-1990s, including:

To what extent has the exclusionary culture of the upper echelons of the Civil Service persisted in the context of broader social shifts and an explicit commitment to the introduction of equal opportunity policy in the early 1980s? [And:] Does equal opportunity policy simply mean succeeding on terms prescribed by the men in place?

Watson argued that it was necessary for successful women in the Civil Service to become ‘the right sort of chap ... a profoundly class-bounded, as well as gendered notion, in which people from racial or ethnic minorities have been incorporated at the top to an even lesser extent than women’.

How far this is a fair characterisation of Whitehall is difficult to determine. Studies have looked at gender, ethnicity and socio- economic background as indicators, but the cultural dimension, described by those who felt alienated by it, was sometimes more intangible and harder to trace over time. Its effect on women covered a number of different things: perception of the dominant character or behaviours of people, a sense of exclusion, feeling pressure to conform to behaviour to be able to succeed, or simply not being entirely comfortable with the atmosphere or a general feeling of not fitting in. Our interviews provided examples of how this felt in practice: in meetings, going into a new department or in terms of career progression.

However, interviewees also talked about why such a culture had not affected them, how it varied across departments, or how this dimension was present, and sometimes worse, in other sectors as well. Overall it appeared to people to be more prevalent, in hindsight, during the earlier decades up to the 1990s, but was recognised, particularly at the higher levels in Whitehall, in later decades and as still in existence today.

Turning first to the socio-economic angle, the popular image of the 1960s, 1970s and into the 1980s was of classicist, Oxbridge-educated and cricket-loving mandarins dominating the top of Whitehall. … One can’t really know how many senior officials enjoyed cricket – apart from perhaps counting club memberships in Who’s Who and elsewhere. However, in terms of the advantages of an Oxbridge undergraduate education, one, admittedly imperfect, way of measuring is to look at the educational backgrounds of permanent secretaries. We counted the number of Oxbridge- educated, department-heading permanent secretaries in mid-1979 and the equivalent number in May 2010. It is striking that of each cohort, roughly two-thirds were Oxbridge-educated: 11 out of 17 permanent secretaries had Oxbridge undergraduate degrees in 1979, as compared with 12 out of 19 in 2010.163 Two of the 1979 cohort did not go to university at all, compared with one in the 2010 group (Dame Lesley Strathie – who led HMRC). It is less easy to establish the total numbers who studied classics or Greats, let alone how many used Latin phrases in the workplace.

How well you got on with this environment depended on background more than gender. Some of the female officials we spoke to pondered whether it had helped that they fitted in in other ways. In short, it was about being the right sort of ‘female chap’. This was because, separately from gender, socio-economic background, education and class were strong cultural influences. Anne Lambert told us that she felt her academic background had certainly assisted her integration into the Civil Service in the late 1970s and 1980s:

I was privileged in lots of ways because, it is not just gender, you know – I came from Oxford and, you know, middle-class Oxbridge is ... fairly routine, so the fact that I am a woman is one thing, but there are other things, where I just fit the mould.

Likewise, Sonia Phippard, a Fast Streamer at the centre in the 1980s, told us:

Now you could be a ‘female chap’ quite easily but if you didn’t want to compromise in that way there was a challenge – and whoever you were, it helped if you’d been to Oxford or Cambridge. So the real pressure remained a fairly distinct culture – if you could adapt, you ‘fitted in’, but that actually it could be difficult and very uncomfortable for people from a variety of backgrounds to adapt to that culture. …

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, growing awareness of the effect of culture on gender diversity, and recognition that certain personality traits and characteristics were prized for advancement or appointment to high-flying jobs, had led to the conclusion that women needed extra assistance to develop these traits. One example was that ‘there was a big phase of assertiveness training for women’, which according to Ursula Brennan, appeared to be based on a belief that quieter women were assumed to be ‘mousey’ and needed assistance to conform to the ‘ideal type’ of the ‘showy and noisy’ official you supposedly needed to be ‘to do the private office, and that was a gender thing’.

….

Helen McCarthy, in her history of female diplomats up to the present day, also perceived a continuation of ‘male behaviours’:

Despite the changes which have taken place since the 1990s, including the enshrinement of ‘diversity’ as an organisational objective, at its higher levels the Diplomatic Service is still a male-dominated institution in which male behaviours, attitudes and assumptions inevitably prevail, and this affects all women, regardless of whether or not they have children. It is notoriously difficult to pin down what constitutes this ‘male culture’ with any precision. Some current Diplomatic Service members talk of ‘blokeishness’ or ‘machismo’, of a certain quality of intellectual aggression or tough talking which many women are either unable or unwilling to emulate."

An interesting Twitter exchange in early 2021 drew attention to the frequent use of 'hedge words' - words which soften what we are trying to say - by both lawyers and civil servants. Civil servants' Mandarin, of course, consists almost entirely of hedge words, used pretty well equally by men and women. One commentator noted that it was interesting and probably relevant that both the legal and civil service professions do comparatively well on gender balance. Outside those two professions, women often seem expected to use hedge words when men would not, and so lose some impact. However, as one woman put it, "I tried to adopt the communication styles of my male colleagues .. and well ... suffice to say it didn't go over well".

Harassment

The IfG's Catherine Haddon published this blog in November 2017 reflecting on the then current publicity about the harassment of women in the entertainment industry, politics and other areas:-

'One of the most revealing comments about Michael Fallon’s resignation as Defence Secretary came from Fallon himself, when he said: “The culture has changed over the years, what might have been acceptable 15, 10 years ago is clearly not acceptable now.”

Well, no. It wasn’t acceptable then either. Not for many of the women and men who experienced discrimination or harassment.

In our history of women in Whitehall, we include accounts of the civil service from the perspective of women, intended to compensate for histories that tend to focus on men (who generally reached the higher echelons). ... But in asking about discrimination, we were also told about harassment.

One woman told us about a problem she had with her line manager. Her colleagues said: “Oh yeah, he does that to everybody.” She laughed it off at the time but wouldn’t now. So yes, something has changed, but it isn’t her feeling that was wrong back then – it is the culture that said you just had to put up with it.

We heard other stories – most didn’t make it into the report – mostly from the 1960s to 1990s: unwelcome advances at office parties; who to avoid being alone with. The recollections of these women weren’t that these actions were ok back then, it was that it wasn’t ok to make a fuss.

The account of Margaret Aldred, who worked in the Ministry of Defence (MoD) from the mid-1970s, suggests maybe Fallon is right that, for many in the department, such behaviour was once acceptable. But it wasn’t for her. She describes MoD in 1975 as a place where “institutional sexism bordering on sexual harassment was the norm”. She also describes how slow it was to change and that she left because she wanted to work somewhere where she was treated as “normal’’.

Whitehall has done a lot to change and the new Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson can learn a lot from his own department’s efforts to tackle that culture. Starting with the assumption that sexual harassment is not something that has recently become unacceptable is a good first step.'

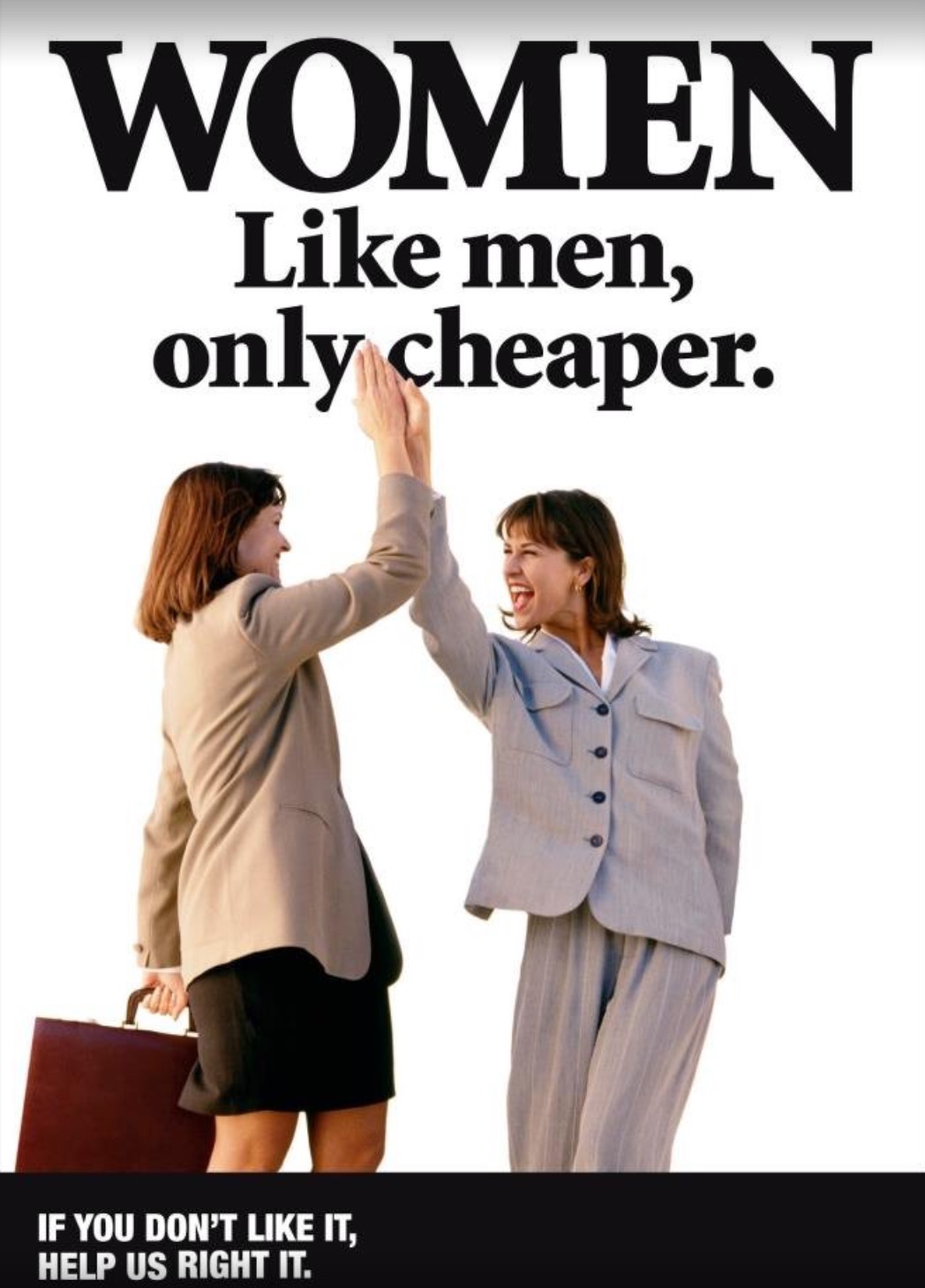

Pay and Pensions

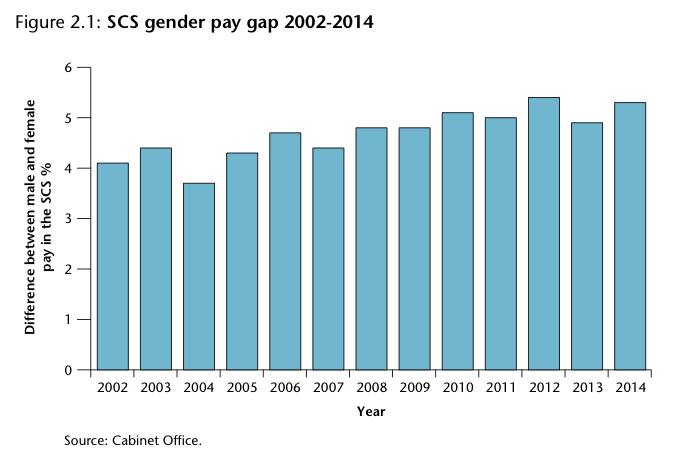

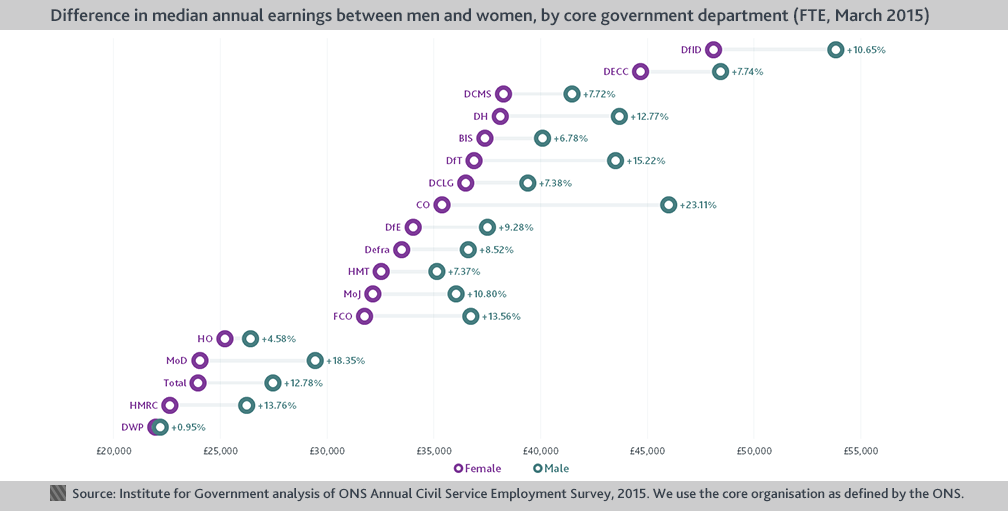

As shown in the following charts, there remains a significant pay gap between male and female civil servants. The gap is smaller in the higher reaches of the civil service.

The Senior Salaries Review Body reported in 2015 that the gender pay gap in the Senior Civil Service (the SCS) is 5.3 per cent in favour of men, compared with 17.5 per cent for full-time employees in the private sector. But the second chart below shows that the SCS gender pay gap widened over the last decade.

The third chart shows how the grade mix varies from department to department, as does the male-female pay differential. Note in particular the Cabinet Office stats. Men clearly still rule this department!

Turning to pensions, I have not seen figures for the civil service only, but the 2011 Hutton Report noted that a median male public sector pensioner received just over £8,000 per annum, while a median female pensioner received just under £4,000 per annum. This gap was explained in part by a combination of more fragmented female careers (particularly connected to caring responsibilities), differential rates of part-time employment (there are currently more than seven times as many female part-time public service workers as male ones) and historic differences in careers and consequently in pensionable pay. (This disparity will presumably become even worse as the effect of career averaging kicks in. Further detail is here.)

More generally, the main reason for the continuing pay disparity has been that many women take time out to have children, and so get promoted later than men. The annual percentage-based increment system then ensures that it takes many years for them to catch up. Alternatively, their next significant pay rise - on promotion - is also a fixed percentage of their previously lower salary, so they lose out yet again. (The Cabinet Office has also argued that externally recruited IT specialists tend to be both higher paid and male.)

Although women civil servants are in general much better treated than their private sector counterparts, it is nevertheless surprising that no female senior civil servant has challenged the system and sought equal remuneration with a male comparator, for there are many examples of women doing exactly the same work as a man but being paid less for doing so. Maybe, like women diplomats, this is symptomatic of the willingness of senior women to meet sexism with pragmatic forbearance, rather than outspoken indignation and litigation ... which leads nicely into the next issue ...

Part-Time Work and Job-Sharing

Alison Wolf (in her 2013 book The XX Factor) noted that the UK Civil Service 'fast track' contains a high proportion of very talented women who are attracted by good maternity leave and the genuine willingness of their employers to allow them to work part-time or in carefully-constructed job-shares. The same, if not more so, applies to the Government Legal Service. Almost all these younger women - and almost all without complaint - saw themselves (and not their male partners) as the primary parent.

Alison (later Lady) Wolf suggested in the same book that job-shares were more expensive and inconvenient than having one person do the job, but I am not so sure. My experience as an employer was that 4-day week part-time staff (men and women) in practice delivered just about the same output (if that is the right word) as their full time colleagues, and were generally very willing to work hard from home when that was necessary, as it usually was. But the attractions of not having to attend the office 5 days a week were adequate recompense for the lower pay. I do not know if something similar applies to job-shares, but it may well do.

However, for various reasons which are hard to pin down, it becomes increasingly difficult to work part time as one rises through any organisation, including the Civil Service. And senior civil service pay is much lower than private sector pay for similar levels of responsibility, so it is harder for senior female civil servants to afford the intense domestic support that is purchased by their counterparts in the private sector.

It May Be Getting Worse

The 2015 IfG report expressed real concern that there was increasing blokeishness at the top of government:

"Interviewees talked about the influence of some at the top of the organisation in changing the culture there, in particular of Gus O’Donnell’s tenure as Cabinet Secretary from 2005. One former Permanent Secretary felt that there had been a genuine effort under O’Donnell’s leadership to foster a cohesive and open culture among the Permanent Secretaries Group:

When I was there, Gus tried to make those meetings [of permanent secretaries] what I would understand a [to be] senior leadership meeting for the system. He encouraged people to be very open ... Gus tried really hard. He tried to bring endeavour, he tried to make those proper leadership meetings, he tried to get honesty and he tried to encourage sharing and all of those sorts of things.

However, it was their view that, following O’Donnell’s retirement, these practices had not been preserved and that this had an impact on how the Permanent Secretaries Group interacted subsequently. What factors may have had an effect and to what extent was beyond the remit of our history. But Jill Rutter has also noted the reversal in numbers of female permanent secretaries after 2011, pointing to the lack of a ‘talent pipeline’ to embed the advances in diversity.

… Some even suggested there had been a regression in SCS culture in recent years:

Things have changed again, particularly over the last five years ... I have seen the culture become more and more macho. The rise of certain individuals, male, white and hugely opinionated, who do not like anyone questioning them, challenging them, has put us back to the Dark Ages. Women are back to being told they are mouthy, aggressive or not leaders when they disagree or display softer inclusive leadership skills. …

Bringing the story up to the present day, the Hay Group report of 2014, like our interviewees, observed that the Civil Service performed well in promoting women into senior positions, relative to other public and private sector comparators. However, it concluded that its ‘culture and leadership climate are preventing talented women from progressing into more senior roles ... many people, and women in particular, do not believe the rhetoric on policy, promotions, or what is valued in the SCS. Accordingly, many choose to opt out.’

Many of these barriers have existed in some form for decades. As we have seen, there is a strong historical connection between barriers to diversity and the pervading culture of Whitehall. This was not, of course, a barrier to all, nor is it true of the whole Civil Service, but it was still a recognisable feature across the period."

And it is worth noting that, as of 2015, there has not yet been a woman Cabinet Secretary, Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, or Permanent Secretary at the Treasury or Foreign Office, nor have any of the four most prestigious ambassadorships (Paris, Washington, and the Permanent Representatives to the EU and UN) ever been held by a woman.

It was therefore interesting that The Times reported on 31 January 2014 that the Cabinet Office was to spend £100k to try to determine why many able women are failing to break through the glass ceiling in Whitehall, following a claim by former-Permanent Secretary Dame Helen Ghosh that government cliques had hampered the rise of women in Whitehall. She argued that politics is driven by networks, and and that women were unable to use them in the same way as men.

Daniel Fitzpatrick and David Richards published an interesting paper in early 2019 and concluded that:-

- women in the Civil Service continued to be concentrated in the lower administrative grades, and less well represented in the higher grades;

- there was a continued general upward trajectory of female representation in the SCS between 2010 and 2015;

- although 40% of the SCS were women, so constituting a critical mass of female talent in the pipeline, the top positions of permanent secretary and director-general continued to be male-dominated; and

- gender imbalances were more prominent still when appointments by-passed the procedures for free and fair competition.

Their paper contains a detailed commentary on, and analysis of these issues.

Statistics

Detailed statistics, for instance about the numbers of women in the Senior Civil Service, may be found here and in the IfG report.