The Brexit Referendum

It is likely that the majority of 'Whitehall' civil servants voted 'remain' in the June 2016 Brexit referendum, in line with similar demographics outside the civil service, especially in London. But there was a significant minority who supported getting out of the EU, especially those charged with maintaining public order and controlling immigration. Home Office Permanent Secretary, and later Cabinet Secretary, Mark Sedwill, subsequently commented as follows:

What was striking about the Home Office at that time was, probably more than any other government department, there were an awful lot of Brexit supporters in the Home Office. It was a caricature to say that the Civil Service is irredeemably Remain. It wasn’t, and definitely the Home Office wasn’t.

The full Sedwill interview is here.

Civil Service Reform took a back seat following the referendum, but there was some interesting comment etc. over the subsequent months and years, as summarised below.

Theresa May

In the background, of course, was the 'interesting' style of our new Prime Minister, Theresa May who, as Home Secretary, had excluded junior ministers and officials from much decision-making, relying almost exclusively on her two special advisors, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, who also zealously guarded access to her - a responsibility that should have fallen to her Private Office who would have behaved more sensibly. This did not bode well for success in her new role, let alone for relations with her senior officials.

Two straws in the wind caused concern in her first few months. First, she expressed concern that the civil service had sought to define the JAMs - the 'Just About Managings' - about which she had said that her government would be particularly concerned. She seemed not to realise that - if the acronym was to be turned into policy, and implemented by legions of officials - then its scope needed to be defined. (Her predecessor David Cameron had made the same mistake when he had failed to define his 'Big Society'.)

Second, she was angry when she became aware of a memo by Deloittes Consulting detailing Brexit-related strains within government and expressing concern that she drew in too many decisions and details to be settled by herself. She then forced Deloittes to withdraw from bidding for government contracts for six months. It was disturbing that senior officials allowed this to happen as Deloittes had done nothing wrong, and her response probably broke the law in the form of EU procurement rules. As David Lock QC commented "truth telling is not a permissible reason to exclude bidders".

But Mrs May was probably not at fault for the falling out with Ivan Rogers - see Item 17 here.

Helen Ghosh Interview

Recently retired Permanent Secretary Helen Ghosh said this in an interview with Civil Service World in July 2016:

The best minister she worked for: "Michael Heseltine. Undoubtedly. He shaped my view of what a really good minister looks like. I was the junior private secretary in his office in the very early 1980s in the Department for the Environment, and it was great to work for a minister who had a very clear idea about how he would approach problems. He took decisions very promptly, respected officials, worked with them as a team. You also knew that when he went off to Cabinet he had political influence and it would probably happen. It’s exciting when you know your minister will go to Cabinet and win the day, as opposed to vaguely argue for something, probably be defeated, and come back with their tail between their legs."

The pressure of being perm sec at the Home Office: "The issue – and [former Home Office perm sec] David Normington said this to me when I arrived – is that in the Home Office every issue is difficult and contested. He said that success at the Home Office is when your press cuttings are that thick but not that thick. What I am proud of is that when we had a crisis… effectively something then happened and then it did go quiet. Even in that relatively short period of time we dealt with things in a really professional way."

Being a role model for women: "I always thought that women have to show other women that being a permanent secretary is an enjoyable thing to do, and I sometimes wonder whether some women looked up to us and thought: 'Blimey, do they look as though they are enjoying it?' I always thought I have to look, even in the tough times, as though I am really enjoying it. I wonder whether some of the women just looked at us and thought: “I don’t know whether actually this job is particularly enjoyable… perhaps I’ll go and do something more enjoyable instead.”

Francis Maude’s reform agenda: "I do think the civil service, from the coalition government onwards, lost self-confidence. We had a very confrontational civil service minister in Francis Maude. I regret the fact that we didn’t, as an organisation, as an institution, grab the reform agenda ourselves and run with it more than we did. We allowed ourselves to be kind of responsive rather than come forward as collectively as we could well have done. We lost the agenda, we gave it up, and I think that disillusioned some people."

Regrets from her time in Whitehall: "I remember at a junior level thinking that that particular minister or senior official was talking to a member staff in a way that was bullying or inappropriate and I didn’t stand up for them. It makes me think, should I occasionally have said: 'Don’t talk to X like that. You may be the director general or the minister or the perm sec, but that doesn’t fit with civil service values.' I think sometimes, in the civil service, we are just a bit too deferential."

Meanwhile, in Parliament ...

The PACAC Inquiry

The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee had begun an inquiry into 'The Work of the Civil Service in April 2016. It was given added relevance by the result of the June 2016 Brexit referendum, and publicised by an interesting October 2016 speech by the Committee Chair Bernard Jenkin. He noted that ' In fact, conscious efforts to reform the Civil Service have usually failed. Ironically, this is testament to the strength and resilience of the institution. The Fulton Report became the archetype of a Royal Commission that took minutes to announce and then years to conclude its work, with far less effect than intended. Many of its conclusions and recommendations bear reading today, but have been ignored. For example, its conclusion that the Civil Service was based on the cult of the generalist, with a lack of skilled management, is an all-too-familiar criticism of the Civil Service today.'

Mr Jenkin also noted that his committee's previous Truth to Power report had been pretty well ignored by the Government, even though:

PASC made only one recommendation: that a Parliamentary Commission should be established to take a long-term look at the Civil Service, to examine its nature, role and purpose, and develop a strategic vision for its future. The Committee recommended that this inquiry should include consideration of the relationship between ministers and their officials. It is interesting that Fulton, the last detailed examination of the overall structure, function and future of the Civil Service, was explicitly barred from considering this topic, leaving it unable to tackle the question of accountability. The PASC recommendation was widely supported and was subsequently endorsed by the Liaison Committee in its report Civil Service: Lacking Capacity, which stated that this Commission should be established “as a matter of urgency”

He also repeated his criticisms (shared by many others) of Francis Maude who had been the Minister responsible for the supposed civil service 'change programme' in the previous government:

First, though many of the proposed changes were laudable, they did not amount to a comprehensive corporate change programme, because the approach was managerial, rather than strategic. Secondly, proposals intended to increase ministers’ control over permanent secretary appointments and their private offices gave rise to the fear that the Civil Service is being subject to what Peter Hennessy called “creeping politicisation” and seemed to go against the grain of the Northcote Trevelyan principles, setting many against the plan. Thirdly, the approach failed to address people, and leadership, and there was no coherent or comprehensive analysis of what the underlying problems arising from the culture of the civil service might be. These gave rise to the shortcomings identified in the reform plans including skills gaps, risk aversion and poor interdepartmental working.

Ex-Cabinet Office Minister Oliver Letwin submitted sharply worded evidence in February 2017, complaining about 'deficiencies of training and culture' leading to poor work authorised by senior officials who had been promoted because of their 'willingness to play the game' rather than on merit. The full text of Mr Letwin's evidence is here.

The committee's deliberations were cut short by the 2017 General Election so it could do no more than rush out its 'emerging themes and preliminary findings' in its report entitled The Work of the Civil Service: key themes and preliminary findings. The committee reported interesting differences of view between retired Permanent Secretaries and those currently in post who no doubt felt that they needed to avoid criticising Ministers' handling of the civil service. These paragraphs were particularly illuminating:

"Lord Butler of Brockwell told PACAC that subject specialism was particularly needed in some areas of the Senior Civil Service:

If you are going to be a Permanent Secretary of a Department like [the Ministry of Defence], you need to have had a lot of training and development in the business of that Department. It should not just be thrown open for anybody to apply and the most able person appointed to it regardless of what their experience is. at will not work.

Notably, Stephen Lovegrove, the current Permanent Secretary of the MoD, rejected this view. He told PACAC that whilst having neither defence, nor permanent secretary experience would have made the role difficult, “I do think it is possible to do it as an experienced Permanent Secretary with comparatively little defence experience”.

... ... ...

The three serving Permanent Secretaries who appeared before the Committee described positive relationships between Ministers and officials and asserted that they had never found it difficult to have an open and honest conversation with their Secretaries of State. Other former civil servants, not currently serving, have pointed to a strain in the relationship. In written evidence, Sir David Normington, the former First Civil Service Commissioner and Commissioner for Public Appointments, warns that, while he does not believe there is an immediate threat to civil service impartiality,

I am concerned at what I see as a slow deterioration over time in the trust between Ministers and civil servants: with more willingness from Ministers to criticise civil servants in public; more leaks from within the Civil Service; a greater tendency to hold civil servants at arm’s length and not to form with them the close partnership, on which effective Government relies.

Professor Kakabadse’s emergent findings also reveal that the traditional boundaries between the respective roles of Ministers and civil servants seem now to be less distinct than in the past:

A previously held clarity between Minister and Public Servant now seems blurred, with certain Ministers relying on their Perm Sec, others having a tense relationship with their Perm Sec and others over-involved in details concerning policy execution/the running of the department and not paying sufficient attention to the bigger picture.

Sir David Normington recommended that the rules governing the relationship between Ministers and officials should be consolidated and clarified:

At present the “rules” governing Ministers, civil servants and special advisers are to be found in too many [different] documents ... This makes the rules of engagement easy to misrepresent or evade and there is no clear responsibility for their enforcement. What is needed is, what might be called, a “new compact” between the Government and the Civil Service, bringing together in one place in more compelling language the basic principles of the partnership between Ministers, civil servants and special advisers.

Stephen Lovegrove, however, argued that “too much codification in this area, over and above the standard accounting officer rules, is probably going to be more obstructive than helpful”."

The committee in effect re-commenced its inquiry after the General Election, but focussed on 'Civil Service Capability'. Its progress and conclusions are summarised in later notes in this series.

Michael Gove Article

Senior politician (though not currently a Minister) Michael Gove published a trenchant criticism of the civil service Sir Humphrey needs to learn who's the boss in The Times in November 2016. Many of his specific criticisms rang true - he focussed in particular on major procurements - although a strong case could also be made in Whitehall's defence. In particular:

- The equipment failures that he highlighted (such as the Type 45 destroyer intercoolers) had been designed and built by private sector companies

- The associated weak contracts had most likely been overseen by private sector advisers and/or experts within the MoD recruited direct from the private sector

- Other decisions criticised by Mr Gove - such as to build 'aircraft carriers without planes' - had been largely driven by political considerations.

- These included Michael Heseltine's decision - many years earlier - to grant a 'national champions' warship-building monopoly to BAe contrary to advice from the competition authorities.

But these defences do not in my view detract from the uncomfortable fact that the civil service - including some very highly paid senior officials - in some sense allowed very expensive and dangerous procurement decisions to be made. This points to a failure to manage the procurements effectively, and/or a failure effectively 'to speak truth to power', and/or a failure by Ministers to ensure that the senior civil service is effectively promoted, recruited and managed. Whatever the underlying reasons, Mr Gove was surely entitled to sound very angry indeed.

Procedural Directions

The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee considered a proposal from the Better Government Initiative in the light of Chilcot’s criticisms of Blair government decision-making before the Iraq War. In short, the suggestion was that the Cabinet Secretary and/or individual Permanent Secretaries should seek a ‘Procedural Direction’ when asked to support Ministers operating outside the terms of the Cabinet Manual. However, unlike the already well established Financial Directions, Procedural Directions might be kept quiet until the need for secrecy had passed, but the responsible Ministers would know that they would one day be held to account for their decision. Not surprisingly, the Government did not like the idea. Further detail is here.

The Lancaster House Speech

Theresa May delivered this far-reaching (and arguably disastrous) post-Brexit referendum speech in January 2017 in which she announced that Britain would leave the Single Market when it left the EU. From a civil service point of view (quoting Chris Grey in Brexit Unfolded) 'the process by which she came to her Lancaster House position is noteworthy, if not downright extraordinary. Not only had it not been preceded by any kind of national consultation exercise ... [but the decisions] were taken, in essence by two people [May and her adviser Nick Timothy]. The Cabinet certainly had no chance to debate them. ... Chancellor Philip Hammond explicitly says that there was no Cabinet discussion of what was in May's 2016 party conference speech and implies that the same was so for the Lancaster House speech.' (In her party conference speech Mrs May had given clear priority to the removal of any role for the European Court of Justice, which inevitably meant leaving the Single Market.)

I do not know whether the Prime Minister's failure to consult senior Cabinet colleagues, let alone the wider Cabinet or even the public, was challenged by her civil service advisers, but it surely should have been, perhaps even to the point of resignation. Future commentators might well characterise this apparent civil service weakness as a historic, momentous and calamitous failure.

NAO Report & PAC Inquiry

The NAO published its report 'Capability in the civil service' in March 2017. It made a number of sensible recommendations having noted that (emphasis added):

The capability of the civil service means its ability to implement policy effectively. The civil service needs the right number of people with the right skills in the right place, supported by effective accountability, governance and information. This report focuses on the people aspects of capability – specifically, whether the civil service has the right specialist capacity and skills to undertake all that government wants it to do. … Recent budgetary constraints have meant that departments have had to undertake ambitious transformation programmes to rationalise their organisational structures, change the way they deliver services or add efficiencies to existing processes. Departments have faced significant reductions in their administrative budgets, with corresponding reductions in staff numbers and resources that can be used for learning and development. Departments also need different skills as they introduce different operating models and new technology.

Civil servants are responsible for an increasingly complex range of tasks and projects. Government is asking the civil service to deliver more, even though its size has reduced by 26% since 2006. The work of government is becoming ever more technical, and delivering government policy objectives increasingly needs a response from the civil service. This may be through providing joined-up services to the public, or carrying out programmes that need departments to coordinate their work. Government’s major projects have an estimated whole-life cost of over £405 billion with 29 considered to be complex transformation projects.

Weaknesses in capability undermine government’s ability to achieve its objectives. We have recently seen improvements in how some departments manage projects but we continue to report regularly on troubled projects. Our work shows that many delivery problems can be traced to weaknesses in capability. For example, a lack of expertise in project and programme management contributed to the collapse of the InterCity West Coast franchise competition in 2012. We also found that the Common Agricultural Delivery Programme suffered from a high turnover of senior leaders. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s (IPA) gateway reviews show that skills, management and resourcing are among the top three concerns highlighted by reviewers.

Government projects too often go ahead without government knowing whether departments have the skills to deliver them. Government is seeking to deliver a challenging portfolio of major projects, including Hinkley Point C, High Speed 2, and the Trident renewal. While the civil service has skilled people, many of these projects draw on the same pool of skills. For example, in rail projects such as Crossrail and Thameslink, we have seen skilled civil servants performing a number of project roles or being moved to fill skills gaps for new priorities or projects.1 Government has recently accepted that project leaders and accounting officers need to assess whether projects are feasible at the outset, including whether departments have the right skills to deliver them.

Government has identified three main capability gaps for the civil service [but] Departments do not know what skills they have, whether these are in the right place, and what additional skills they need. We have reported a number of times since 2011 on government’s lack of proper workforce planning and that it does not have a clear picture of its current skills. … Government’s capability initiatives will take time to mature and greater urgency is needed. …

Government does not fully understand the private sector’s capacity to supply skills. … one in four senior recruitment competitions run by the Civil Service Commission in 2015-16 resulted in the post not being filled. Many of these were for senior posts with specialist commercial or digital skills.

Leaving the EU will further increase the capability challenges facing government. The Cabinet Secretary has referred to the United Kingdom’s decision to withdraw from the EU as “the biggest, most complex challenge facing the civil service in our peacetime history”.

The next step is for the PAC itself to report having taken evidence from civil servants and (slightly unusually) having called for evidence from others. Its report will also have a slightly wider title:- ' Civil service capability and the “revolving door” '.

The Better Government Initiative submitted some interesting evidence to the PAC shortly before the 2017 General Election. In their press release, the BGI said that they had ...

'expressed grave concern that a much reduced civil service, faced with the additional demands of Brexit, will be asked to do a job that it is simply not resourced to deliver. Commitments in the election manifestos will further increase the pressure. There is a real danger that civil servants will have to cut corners, with the institution as a whole suffering a serious loss of motivation and morale as it is castigated for the failures in policy and delivery that will inevitably follow.

We suggested a number of steps that could help to limit the damage:

• A “clearing the decks” initiative with all departments putting forward proposals for cutting, scaling back or delaying initiatives already in the pipeline.

• Consistent application of best practice rules and guidance to the remaining business with enhanced scrutiny to ensure that this is being done.

• Strenuous efforts by Departmental Boards and Non Executive Directors to avoid overstretch through the accumulation of new demands.

• Greater transparency through self-assessment of departmental capability reported to the Cabinet Office and high-level peer reviews by departments of each other’s capacity.

• A refocusing of the PAC’s work to concentrate more on the ability of departments to deliver the totality of the demands placed upon them.'

The final recommendation is particularly interesting. Most of those familiar with the work of the PAC recognise that it usually spends far too much time trying to find scapegoats to be blamed for things that have gone wrong - and almost no time delving more deeply into the resource and other issues that led to mistakes being made. It will be interesting to see if the PAC take any notice of the BGI's recommendation, but I, for one, am not holding my breath.

Brexit, Austerity etc.

It wasn't just the NAO who were concerned about the capability of the civil service. The uneven consequences of 'across the board' austerity were increasingly evidenced in the form of problems at the front line, most particularly in the Health and Social Care sectors. Ex-Permanent Secretary Leigh Lewis described the process all to accurately in this extract from a longer March 2017 article in Civil Service World:

In the run up to the Budget it was widely reported that the chancellor had asked all but the "protected" departments to come up with proposals for a further reduction of £3.5bn in spending by the end of the current Parliament. Unless the world has changed utterly since my own time in government, a ritual process will have taken place. To parody only a little, the Treasury will have told each affected department what its ‘share’ of these cuts needs to be. Departments will have responded by describing the likely impact of such cuts, painting a picture of death, disaster and mayhem. The Treasury – inured by decades of listening to such protests – will have ignored the protestations and demanded the number it first thought of. Last minute political haggling – and even, in some cases, threats of resignation – may have secured some alleviation, but not much. And the previously warring ministers – once the spending figures have been announced – will have assured the public that the cuts, while challenging, can undoubtedly be delivered through greater efficiency. And sometimes they can.

But not always. Take the Prison Service as perhaps the most glaring example of this macabre dance in recent years. Between 2010/11 and 2014/15 the Prison Service budget was reduced by around a quarter – approaching £1bn – at a time when prisoner numbers remained at an all-time high of around 86,000. Over the same period, prison officer numbers fell by around 9,500 – nearly 30%. At Pentonville prison – to give one example of the impact of these cuts at local level – it has been reported that officer numbers fell from 280 to 211 between 2013 and 2016, while at Holloway the reported reduction was from 150 to 121 over the same period. The effect of these reductions is now clear; serious outbreaks of disorder, increasing drug and substance abuse and, potentially most serious of all, a collapse of prison officer morale to name but three.

Finally, faced with increasingly lurid and public examples of each, the government has responded by restoring some of the cuts in Prison Officer numbers and implementing unilateral pay increases for Prison Officers in the areas of greatest shortage in what has looked extremely close to a panic reaction. Predictably, the media and the opposition have piled in to attack the government for its incompetence. But the truth is that all governments in recent decades have been guilty of imposing similar examples of short-sighted reductions. Indeed the current crisis in social care is arguably the result of every government over the last thirty years acting with similar irresponsibility.

But senior officials appeared confident that they could cope - or maybe they were complacent. Here is a January 2017 report by Civil Service World of its interview with Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood:

Ministers are planning to shelve "very few" of the government's existing commitments to free up resources for Brexit, Britain's top civil servant Sir Jeremy Heywood has told CSW, in spite of warnings that Whitehall is already overloaded as it prepares for Britain's departure from the European Union. In the wake of the UK's vote to leave the EU, a number of figures have said that the civil service – which has cut headcount by almost 20% in the past six years – is doing too much and will have to pare back some policies to allow for the urgent extra work required by Brexit.

Civil service chief executive John Manzoni has previously described the civil service as doing "30% too much to do it all well", while Sir Amyas Morse – head of the National Audit Office spending watchdog, last year urged ministers to stop asking departments to run on "perpetual overload". But ... Heywood made clear that the government intends to press ahead with the majority of the Conservatives' 2015 manifesto goals, while also working on Theresa May's new policy priorities and implementing Brexit. “Obviously, when you have a new government with a new set of priorities the logical question is: well, do the old priorities still stand and how many of these new priorities become even more important than the pre-existing workload?" he said. “So we’ve had those explicit conversations. And I think the honest truth is that very few of the original set of priorities can be dropped. "The prime minister feels very strongly that she and other ministers were elected on a Conservative Party manifesto that must still stand. So, of course, she’s added some further priorities and we’ve got the Brexit programme as well. But, you know — one way or another we are going to deliver that package. That’s the civil service’s job.”

Concerns have also been raised since the Brexit vote about whether a smaller civil service has the resources to handle the task before it. But despite some speculation that the referendum result might prompt a rethink of departmental spending plans, most of Whitehall is still working to deliver tough settlements agreed with the Treasury in 2015. Heywood told CSW that it was important for civil servants to be "resourced to do the job that they’re asked to do", and said individual departments were free to "make their case for more resources to the Treasury". But he added: “The Treasury of course, and I as head of the civil service, expect that there will be some reprioritisation. This is not just a case of extra resources. Because, as a whole, we’ve got to meet the fiscal ceilings that we’ve got. And the civil service certainly can’t be exempt from the overall requirement to control public spending. "So we will live within our means, we will try and reprioritise, and where a case can be made for extra resources, as in the case when you’ve got a new department like DExEU or DIT, of course the Treasury will find a way of making that happen out of the normal reserve.”Heywood estimated that the civil service "at the moment requires 1,500 to 2,000 extra roles", including "another 100 senior civil servants" – but he said Whitehall was already "two-thirds of the way" through filling those posts, and praised the way the organisation had stepped up to the challenge of Brexit. “I think we’ve shown once again over the last few months, which has been a very, very intense period, just how effective we are in supporting an incoming administration because, let’s face it, we’ve got a new prime minister, a new set of ministers, a completely new agenda. We have turned on a sixpence and are now focused very much on that and serving the country in that way."

Dave Richards and Martin Smith published a blog towards the end of 2016 discussing the way in which Whitehall (by which they meant Parliament, Ministers and officials) would need to change to cope effectively with Brexit and all its consequences. Here is a brief extract:

The current climate requires a sea change in Whitehall. … This would require a fundamental move from hierarchical bureaucracy [and deployment of skills that] focus on specific problems, … flexibility, and rapid intervention. Expertise would no longer be located within a department, but to teams deployed to deal with particular projects or intractable problems. It would, however, require a very different ministerial-civil service relationship and … an overhaul of the Westminster Model.

Recruitment Rules Relaxed

Despite this optimism, the Civil Service Commission were asked and agreed that civil service hiring rules could temporarily be relaxed so that senior staff could be brought into departments on salaries of up to £142,000 without having to go through an open recruitment process.

Dodgy Statistics

There was a growing feeling that civil servants were paying less attention to the need to publish accurate information and were instead over-willing to publish dodgy data that supported Ministers' (or even their own) preconceptions. There was an example of this in January 2017 when the Cabinet Office (no less) published a report which included some sensible things about the management of information but also included some unnecessary and ill-informed comment about policy making in government together with a figure of £500 million on "wasted effort from recreating old work”- based, according to a footnote, on a Cabinet Office estimate. The Times unsurprisingly built a story around the loose comments on policy making and this estimate. Equally unsurprisingly they asked the Cabinet Office to stand up their own “estimate”. A Cabinet Office spokesman apparently said on the record - without apparent shame - that “This is an entirely hypothetical figure which is not based on an analysis of actual working practices”.

Departmental Priorities and

Permanent Secretary Objectives

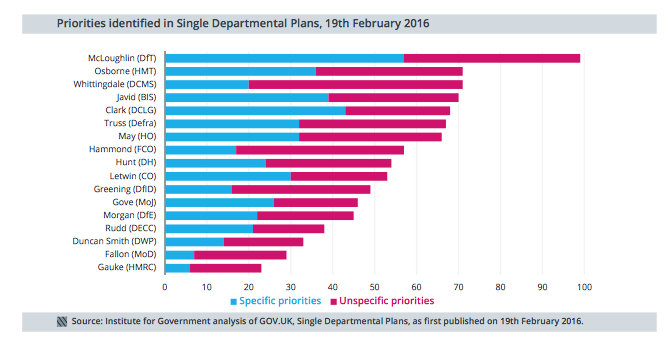

Everyone who has ever managed anything knows that it makes no sense whatsoever to have a large number of 'priorities' and objectives. Unfortunately this message gets lost when Ministers and senior officials sit down to draft departmental plans etc. They are unwilling to put on the record that any one activity or objective is less important than others, and/or they succumb to the 'more on' tendencies pervasive throughout the civil service, neatly summarised here. The Institute for Government was scathing when it drew attention to this problem in their 2017 Whitehall Monitor:

'Unfortunately, the first SDPs (Single Departmental Plans) published in February 2016 gave no sense of priority. Despite the hard work of civil servants in developing them, ministers appeared to have shoehorned as many of their manifesto commitments into the SDPs as possible: Patrick McLoughlin, then at DfT, had close to 100; Theresa May, then at the Home Office (HO), had more than 60. The Institute for Government criticised SDPs as ‘little more than a laundry list of nice-to-haves’; the Public Accounts Committee has argued that they ‘do not enable taxpayers or Parliament to understand government’s plans and how it is performing’. Only nine departments still in existence appeared to have updated their plans between Brexit and the end of 2016, and no public plans exist for the new Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU), Department for International Trade (DIT) or Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

The SDPs show that the way government measures its performance has gone backwards, even from the Coalition’s suite of Departmental Business Plans and impact indicators (which, despite early promise, were difficult to use and were consequently neglected). Without clear, sensible and transparent plans and measures it is impossible for the centre of government, departments themselves, Parliament or the public to understand how well government is doing and hold it to account.

...

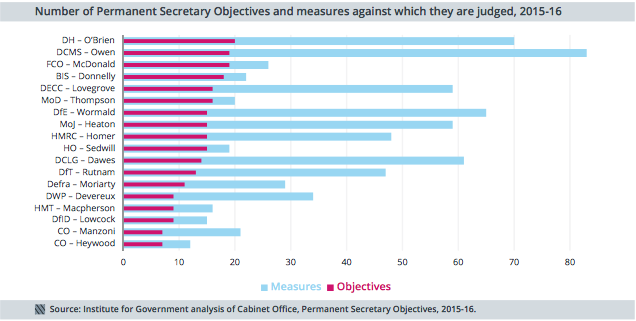

Last year, the number of objectives for each permanent secretary varied between seven and 20, with an average of 14. This is up from the previous year’s more sensible average of nine, which implied some prioritisation. The number of measures against those objectives has spiralled even further: an average of 39 in 2015-16, up from 15 in 2014-15, a ludicrously high number that suggests that a multitude of tasks and issues are being lumped into each supposedly single ‘objective’.

This is a disappointing decline in quality. In 2013-14, a review by Mark Lowcock, Permanent Secretary at DfID, introduced a more sensible approach, reversing the tendency towards too many objectives and not enough measures. Unfortunately, the 2015-16 objectives do not continue this trend, and instead revert to the meaningless.

Departments are inconsistent in how they format and organise their objectives. They confuse measures, milestones and means of reaching them. The inconsistency across departments and the sheer number of objectives raise doubts about how useful and usable they are – and, crucially, whether they are actually being used to measure performance (one of the FCO’s objectives was to raise engagement scores to ‘x%’).'

'All Change'

The Institute for Government published its 'All Change' report in March 2017, giving an interesting insight into recent failures of policy making. This IfG summary says it all:-

All Change lays bare the staggering amount of change in key government policies over the last five decades. The report examines three policy areas which have experienced near-constant upheaval: further education, regional governance and industrial policy. For example, the last 30 years have seen 28 major pieces of legislation relating to further education led by 48 secretaries of state. And there have been three industrial strategies in the last decade alone.

The cost of all this reinvention – both human and economic – is high. Government can and must safeguard against wasting more time, money and resources on endless changes that result in little progress.

This churn is not simply a result of changes in government. It highlights persistent weaknesses in our system of government: the tendency to change and to recreate rather than commit to stable, well-evidenced policy.

Extended Ministerial Offices

The Conservatives' 2017 election manifesto contained an announcement that EMOs were to be scrapped. Whatever the merits or otherwise of this decision, it was a shame that this was apparently going to happen without any proper evaluation - or consideration of the problem that they were intended to address - or consideration of what might replace them.

(See Notes 12 and 16 to read about the origins etc. of EMOs.)

And then ...

... came the 2017 General Election. Note 18 picks up the story from then on.