There is persistent criticism that the civil service too often fails to identify innovative solutions to policy problems. There is some truth in this but this is not due to the character of individual civil servants. It is inherent in the way in which the UK is governed in contrast, for instance, to New Zealand.

Experienced officials are well aware when systems need to be improved, and welcome ministers' and others' encouragement to innovate. Tom Legg, for instance, tells how his predecessor Derek Oulton, persuaded Lord Chancellors to get on with major restructurings of the legal system. Tom himself recommended the creation of the Ministry of Justice from the late 1960s, and the Supreme Court a little later, both many decades before ministers felt able to make those changes. Other notable examples include Robert Fitzroy who created the first weather forecasts (meeting much scorn and opposition at the time) and Charles Sisson who recommended the creation of the Health and Safety Executive.

So why does the civil service (as distinct from individual civil servants) appear so risk averse?

- We work for politicians who in turn work in an adversarial and confrontational environment, under constant media scrutiny. It is the duty of the Opposition to oppose. New ideas are swiftly attacked, improvements are regarded as evidence of past failure, debates about the merits of particular proposals are seized upon as signs of divisions within Government, and mistakes are mercilessly exposed and criticised.

- Innovation requires officials who know the systems they are advising on. But many ministers - particularly nowadays - do not like to work with expert officials who know more than they do, and they do not like to be out-shone by exciting, achieving and innovative officials.

- Rapid ministerial turnover doesn't help, either. Ministers who are 'learning on the job' are unlikely to have the necessary experience, knowledge and instincts to drive through innovation against entrenched opposition outside their department.

- Many ministers are nervous that they might be exposed to criticism for considering some new idea which has not yet been properly thought through. Any potentially controversial idea that cannot be kept entirely secret is therefore best left well alone.

- Modern Spads are more likely than their predecessors to brief the media about internal policy discussions. This might inhibit private discussion of controversial proposals.

- Civil servants are part of a profession, and cannot afford to alienate colleagues with whom we might have to work very closely for years to come. Also, our professional and financial rewards come mainly via promotion. It is therefore crucially important that we do not do anything which might upset a senior colleague, and in particular our manager and our Permanent Secretary. We therefore: do not encourage internal challenge; hesitate before saying anything which might be construed as foolish by any senior colleague – most of whom will be older than us; and are reluctant to draw attention to colleagues, or parts of a department, who are performing badly – and yet this is often a necessary precursor to real change.

- We work within quite distinct Government departments, with quite distinct budgets and for Ministers who are usually in competition with their colleagues in other departments. We develop a loyalty to the organisation, to our staff, to our budget and to our Ministers, which tends to inhibit free thinking.

- It is a firm rule that the Treasury have to be consulted before we commit resources to anything ‘novel or contentious’. And if that doesn’t deter us, a colleague will soon remind us that our Permanent Secretary is directly accountable to Parliament for the way in which we spend public money. Mere suspicion that we might cause the Permanent Secretary to be asked questions will cause our judgement to be questioned.

- Common sense, bolstered by the doctrine of collective responsibility, means that it is necessary to consult, often quite widely, before becoming committed to any significant new policy. Colleagues will inevitably express various concerns and, although it might be possible to address each of them, the effort of doing so can be quite daunting.

- Our work is dominated by major and apparently unquestionable policies, including those in manifestos. There are therefore significant limits to the extent to which we are permitted to think the unthinkable.

As an example of how ministers hate mistakes, and thrash around looking for someone to blame, look at how quickly the excellent Head of the Parole Board, Nick Hardwick, was sacked by minister David Gauke following the decision to release multiple rapist John Worboys - even though Mr Hardwick had not been involved in making that decision, and the Board typically took 25,000 decisions a year with very few complaints. Mr Hardwick accepted the decision but warned that his dismissal raised serious questions about the Parole Board’s independence.

Another example was the sacking by minister Ed Balls of Haringey Director of Social Services Sharon Shoesmith following the death of 'Baby P'. She subsequently received substantial compensation.

- Note that neither minister was thought to be particularly weak. Indeed, both were very well regarded. But they nevertheless felt it necessary to cave in to pressure to 'do something' - other, of course, than resign themselves!

Against the above, let me make some important points.

- Other organisations find it equally difficult to foster internal challenge and innovation. Indeed, variations on all the above problems, apart perhaps from the first and fourth, can be found in most other large professions and organisations.

- There is nothing in our two key professional duties (to give independent, balanced advice, and to implement Ministers’ decisions, even if we have advised against them) that stops us being innovative.

- There is no suggestion that we should all become innovative or creative all the time. But those of us that are innovative – and when we are innovative – need to operate in a supportive environment.

- Being innovative is not the same as being entrepreneurial. Whatever they may say, no-one, and least of all our Ministers, want us to treat public money as if it were our own, or do deals other than within clearly established boundaries.

So here are a few thoughts that may help you create innovative teams.

The key point is that teams become innovative when they are well led, truly empowered within clear boundaries, and measured by results. In addition, you have to encourage a little rebellion and a questioning culture. Allow people, if they wish, to squirrel away a little time to work on pet projects. Expose problems – otherwise they will not get solved – and reward innovation through pay and promotion as well as in less tangible ways. Do not create a team that is excessively harmonious, for this stifles innovation.

Above all, do not kill off new ideas and new thinking before you and others have had a chance to think about whether - despite your initial reaction - there might be something in them. As Charles Brewer once said:

A new idea is delicate. It can be killed by a sneer or a yawn; it can be stabbed to death by a quip and worried to death by a frown on the right man's brow.

Planning

Next, I want to stress that the first thing you should do, once you have a bright idea, is to decide the extent of the likely opposition and plan a strategy for overcoming it.

Don’t be reassured by Ministers’ and senior colleagues’ well-meant protestations that they adore innovative and risk-taking officials. In practice, innovation is fine if there is relatively little political interest in the activity. It is also easier to innovate if you are working closely with customers, and responding to clear customer pressure. That is why colleagues in many agencies and local offices find it relatively easy to innovate, if their head offices do not hold them back. In contrast, just imagine the obstacles that would face the Prison Service in the unlikely event that they found a way of halving the recidivism rate, but at the cost of doubling the number of escapes. They would have to plan their innovation strategy very carefully, enlisting strong Ministerial support, gaining buy-in within the wider Service (which would take time), and – above all – becoming very innovative in managing their relationship with the media.

This is, incidentally, one of the benefits of having prisons run by private contractors. Some (not all) of these prisons are amongst the best in the UK because they pay better, they attract and keep more experienced staff and, because the don't have to clear every idea with Whitehall, they have been quicker to introduce modern technology etc.

Next, let's look at two particular threats to innovation:- the fear of risk and departmentalitis....

The Fear of Risk

Because Ministers are publicly accountable, they are understandably reluctant to make mistakes that might expose them to criticism, even if only with the benefit of hindsight. Their officials should therefore be aware of the risks associated with various courses of action. But you will never achieve anything if your principal career objective is never to make a mistake. You should therefore aim to be risk conscious rather than risk averse. It is helpful to think in terms of a spectrum of risk.

There will be high risk if the suggested action will commit a great deal of money or other resource; if the repercussions from the action are unpredictable; if there is a history of serious error in this area; if the decision is of significant political or media interest; if there will be many losers and/or if there will be a small number of heavy losers. If these features are present then do not rush the decision. You should consult and plan very carefully, and if possible test the water by piloting any new scheme or activity, so as to test its practicality in the real world. In other words: ‘Don’t bet the business’.

There is low risk if an error would have little cost, is unlikely, could easily be corrected and/or is of little political or media interest. In this case, do not delay and keep consultation to the absolute minimum. Get on with it! Far too many civil servants agonise at length over minor decisions, and rush the major ones. They obey the well known law that the time devoted to the decision is in inverse proportion to its importance. Feel free to break this particular law!

But there are many intermediate cases where decisions carry medium risk. In these cases you should ask ‘why not?’ rather than ‘why?’. Try out the idea on one or two interested observers, without exhaustively arguing the pros and cons. If there is no strong opposition, then again get on with it without further consultation. Otherwise, think through the issue again – and especially those aspects that have concerned those you have consulted.

There is no need to worry all the time about possible Public Accounts Committee or media criticism of minor decisions. Such criticism is generally concentrated on major decisions where the risks were clearly high, and the spending or action clearly inappropriate. Indeed, Sir John Bourn, head of the National Audit Office, said:

‘The problem is not that the Whitehall culture is risk averse .... Rather, it is risk ignorant. It takes the most fantastic risks without knowing it is doing so.’

Therefore, as long as you are conscious of the scale of the risk associated with your decision, and prepared to justify your decision on that basis, whilst recognising that others might well have decided differently, you will not receive serious criticism. All this was neatly summarised by Sir David Omand who, when Permanent Secretary at the Home Office, told his colleagues: ‘If you are not making mistakes, you are not trying hard enough’.

Departmentalitis

The strongest opposition to any innovative policy will inevitably come from other departments, fueled by departmentalitis. Gerald Kaufman MP first drew attention to this debilitating Ministerial disease in his excellent book How to be a Minister:

If you contract departmentalitis you will ruthlessly pursue your own department’s interests even if another department has a better case: quite simply, your department must win . . . you will forget that you are part of a government, that the fortunes of the government are more important than the fortunes of your own department.

But the disease is also endemic amongst officials. We kid ourselves that we run a finely tuned machine, coordinating and consulting effectively with colleagues elsewhere in Government. The truth is that large groups – and indeed whole departments – all too often compete with one another with the result that progress is too slow and we make too many mistakes. As a result, the whole system can begin to break down, and can sometimes break down completely.

The correct treatment for this disease is to refuse to play our cards close to our chest, and refuse to seek power by failing to share information. Remember in particular that Ministers may not order us not to consult or give relevant information to colleagues who have a right to be consulted or to know what is going on. It is of course sometimes sensible to work up a proposal before showing it to colleagues. But you may not collude in a ‘bounce’ and if you feel that colleagues in another department would expect to be told about a proposal, then you must tell them. Officials in different departments should also try very hard to resolve differences without involving Ministers. It is stupid and inefficient to conduct an argument between officials through Ministerial correspondence. This should be reserved for genuine debate between Ministers.

Of course it is no bad thing to become emotionally committed to achieving your, or your Minister’s, objectives, as long as you remain politically impartial, well-balanced and professional. But you should not set out to browbeat colleagues by arguing as if your preference is self-evidently optimal. Such certainty can sometimes impress colleagues, and can sometimes sway decisions. But it is unprofessional and leads to decisions that are not soundly based. If your Minister’s view does not seem to stand up to critical onslaught, you need to go back and discuss the problem. You should not simply try to bulldoze his or her view through.

And we should not hesitate to seek help from colleagues, even at the risk of appearing a little silly. Colleagues collectively have a wealth of knowledge and experience. Even if the problem is quite novel, they will have ideas about how you might tackle it. Indeed, many problems melt away if you simply seek help from colleagues. Almost everyone is more than willing to help, if they are approached in the right way. Indeed, it is often a very good idea to brainstorm an issue or to think aloud. But you should flag up very clearly that this is what you are doing, or else colleagues will think that you are delivering a considered view, and will not be impressed by your more hair-brained ideas!

You may occasionally come across someone – perhaps in a central department or in an influential position elsewhere in your department – who will seem to give you a direct order that you are not happy to accept. Remember that they cannot do so. No official other than in your management chain can give you an order, even if they are in Number 10, in the Cabinet Office, or even in your Solicitors’ office. They can draw your attention to their Minister’s views, or to established policy, or to the law, and you will usually wish to take careful note. But in the last resort you must be guided by your own professional opinion. If you were to follow their advice, and they were to turn out to have been wrong, you could not subsequently blame them. If they continue to press their case, and you remain unpersuaded, you should consult Ministers or (in the case of legal advice) your department’s senior legal adviser.

Finally, a word about dealing with the Treasury and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO - now FCDO). Officials from these two departments tend to wield more power than others. This derives from the status of their Ministers and, in the case of the Treasury, from the fact that they act as HMG’s banker. But the nature of their work means that some of them have little first-hand experience of their subject, or of achieving change. They are therefore required to question your policies without being expected to know the underlying facts. As a result, a small minority of Treasury and FCO colleagues give the impression that they believe that other departments are not clever enough, are not critical enough and do not work hard enough. In practice it is not too difficult to prove them wrong, as long as you are indeed fully on top of your policy issues, and the associated facts. If they can ask a relevant question that flummoxes you, you have only yourself to blame. The vast majority of Treasury and FCO staff are in fact very professional, experienced in their fields and invaluable colleagues. You should therefore treat them as equals, and expect them to treat you likewise.

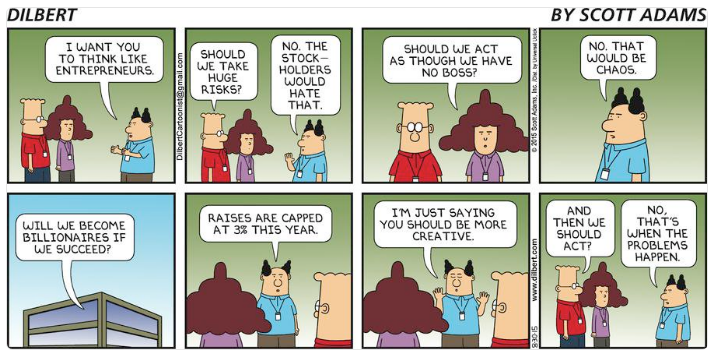

PS - Don't be like this guy!