Natural disasters and other crises require rapid responses which involve making difficult judgements. Sir David Omand reminded Ministers that:

You are going to behave rather differently; the pace of decision-making is going to be much faster than you have been used to; the mechanics of your relationship with your officials are going to be rather different, and very importantly, you are going to have to take more decisions on less information than you have been used to. That last point means you have to stick your neck out ... it is about risk management. You do the best you can, but it may or may not be the best decision at the time and you are not going to know that as you take it... You have to live with that and just get on. That is not how most policy-making process works.

Officials need to plan thoroughly for such events, and ensure that the necessary resources will available to mount an effective response. They should 'prepare for the worst and hope for the best'.

If and when a crisis occurs, it is vital that both Ministers and officials apply the lessons learned by those responding to previous crisis. This is not a time to believe that 'you know better'. Here, then, is detailed advice from those who have gone before. It draws on a number of sources including Catherine Haddon's Political decision making in a crisis.

(The notes and examples were added to help illuminate the Government's response to the 2020 Covid-19 coronavirus epidemic.)

1. Plan and Prepare for Possible Crises

Officials (and ministers) should practice (‘game’) responding to crises. The Civil Contingencies Unit's mantra is 'Prepare for the worst and hope for the best'.

You should:-

- assume that the crisis will hit when your organisation is in some ways unprepared, for reasons outside its control.

- assume in particular that key team members and decision makers will not be available.

- Note that the Prime Minister and several other Ministers and senior advisers became unavailable during the Covid-19 crisis.

It is hard to overstate the importance of practising responses to possible emergencies. Voluntary reports to the US Aviation Safety Reporting System showed that 86% of flight crews handled 'textbook emergencies' well. But only 7% of non-textbook emergencies were handled well. 93% of crews were overwhelmed by situations for which they had not prepared. You can see very similar problems in departments' responses to problems which could have been foreseen if they had undertaken sensible emergency planning . See also failure to learn.

They should also:

- be aware that the first instinct of Ministers will be to limit the reputational damage that they think is going to happen to themselves rather than focus on how to fix the problem.

- prepare public responses to foreseeable damage caused by your organisation.

- not let lawyer-driven responses – seeking to downplay legal liability - cause large reputational damage.

No plan will survive contact with reality. But if there is no plan then reality will take over with disastrous consequences.

Get your most sceptical staff to check, from time to time, that the detail of the resilience or crisis management plan is up-to-date, sensible and appropriate. Red teaming might be useful.

- In the US, following Hurricane Katrina, mandatory evacuation led to all vehicles leaving New Orleans well in advance of the plan’s deadline. Unfortunately the plan made no mention of the need to evacuate those residents who did not have vehicles within a similar timescale.

- In the UK, there is some concern that the effectiveness of the response to any energy supply crisis would depend too much on the cooperation of the private sector.

Beware the Prevention Paradox. Activity and expenditure aimed at avoiding future disasters seldom generates political credit. (Example: Y2K). But failing to act will eventually wreak much greater havoc.

Examples

- Inadequate pandemic planning/implementation before COVID-19;

- Also light touch regulation before the 2008 financial crisis … and Climate Change?

You can’t see everything coming. You cannot stockpile in anticipation of every disaster. But disaster planning must include building in some resilience. Do not eliminate all slack and redundancy in key systems, nor in the emergency and armed services.

Examples:

- The NHS and Care Home Sectors were insufficiently resilient to cope with a sustained Covid pandemic.

- Ministers were proud of the fact that the pre-Covid NHS had very low costs, by international standards, and high bed occupancy rates. c.40,000 hospital beds had been removed in the previous decade. Then a pandemic arrived.

- Whitehall had only limited pre-Covid knowledge of, and contacts in, key sectors and industries.

- An example from history is this quote from a biography of Vernon Kell, the founder of MI5:

(Senior officials in Whitehall were traditionally expected to have a deep knowledge of their subject areas, to have travelled throughout the UK and internationally, to have spent time in schools, factories etc., and to know the key leaders and thinkers in their areas. But much of this activity appeared unnecessary – frivolous even - during quiet times especially when civil service numbers were being cut (down 28% 2005-2016). And subject expertise was not always valued by Ministers. So Whitehall lost the background knowledge, resources and networks needed to cope with unforeseen crises.)

'[Our 1914 army] required more and more men. Without conscription we would never get enough of them. The posters displayed on all the hoardings with Lord Kitchener's face looking forcefully at us ... had brought in a great voluntary army, but all these efforts would have been infinitely more effective had they been planned, years before, to meet an emergency.'

2. Ask whether you have the necessary powers

Make sure you have the statutory powers – and discretionary powers - necessary to respond to any plausible crisis.

- Legislation will provide strong guidance but you may, for instance, need to ask the security services to act without specific authority. As an American Judge opined – “The constitution is not a suicide pact”.

- I understand that the UK authorities did not initially have the powers necessary to resolve the run on Northern Rock.

Such powers should be subject to appropriate political oversight. It is for ministers to judge when to go to Parliament but, if they are reluctant, you might need to gently encourage them.

- Internal response planning discussions, including with Ministers, should not be disclosed unless/until their existence will not cause damage.

HMG can if necessary (and with Parliamentary approval) legislate very quickly. It also has powers, in the Civil Contingencies Act and other legislation, to act ahead of Parliamentary approval.

Internationally, the UN Security Council can act including by giving strong powers to an international authority under Chapter 7 of the UN Treaty.

Serious crises are likely to require the government to take steps which would be unacceptable in normal times, such as restricting civil liberties, allowing police searches, and slaughtering animals. These actions are much more likely to be accepted if the general public is already inclined to trust both ministers and officials to be doing the right thing and acting proportionately. Advance planning, involving ministers - see further below, offers an opportunity to draw attention to this lesson.

Covid-19

The necessary legislation appears to have been in place and was triggered as soon as it appeared that someone might refuse to remain in quarantine.

- The key legislation is in Part 2A of The Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984.

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 were made under the above Act and signed by the Health Secretary at 0650 on Monday 10 February 2020.

- In combination, this legislation confers very great powers on doctors, the police, local authorities and magistrates.

- In particular it empowers a constable to use reasonable force to detain anyone whom they suspect might be infected.

- And the Secretary of State or a registered public health consultant may require screening and isolation of suspected carriers, and can require them to answer questions, provide documents etc.

- Magistrates may require seizure, disinfection quarantining etc. of ‘things’ and premises.

- 11 months later, though, ministers had constructed a huge regulatory edifice following 65 revisions to the initial lockdown laws. It is at least arguable that this was over-complicated.

- The Johnson government did not have a great reputation for honesty and this probably meant that some of its responses to the pandemic were less effective than might otherwise have been the case.

3. The Initial Response

It can be difficult to know how to react to a rapidly growing threat. There is often no option that will not cause significant harm. Epidemics, for instance, will kill people if you don't damage the economy by implementing a lockdown. In general, though, the sooner you act, the less the harm..

There should be well-practised plans to help you cope with predictable emergencies, together with appropriate resources. Even so – and more likely if not so – you may need to take strong action early in the crisis, when the threat appears small. But you should nevertheless take the time – maybe just a few hours or a couple of days – to listen to experts, to discover, to organise, and to absorb what information and knowledge is available. Then act decisively.

Ignore those that tell you not to ‘over-react’. A significant proportion of the population and the media will continue to deny reality, even as things fall apart. Psychologists call this normalcy bias. A nice (fictional) example is here.

Others accept or acquiesce in the new reality far too easily.

- Example:- Well over 1,000 were dying each day at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak, and yet this horrendous total seemed to be accepted with a shrug by large sections of the population.

If your decisive reaction prevents the danger from happening then you will be accused of over-reacting etc. etc. This is called the prevention paradox. This is not a good reason to delay.

Equally, we become more comfortable with risks as we get used to them. We also get better at responding to familiar risks. So your initial response might in time become seen (quite wrongly) as over-protective. Again, this is not a good reason to delay. But it may been that less firm measures might be appropriate once the nature of the risks have become clearer.

- Examples:

- It looks as though the UK should have locked-down to impede the initial spread of COVID-19 maybe a week earlier than it did.

- The UK population seemed to be less worried about the second and subsequent waves. This may have been evidence of excessive complacency which might have led to reduced compliance with guidance and legal restrictions, compared with the initial lock down. Equally, though, it may have been evidence of learning to live with the risk - agreeing to meet outside (where the risk of infection was less) - or young people still meeting in groups (knowing that the risk of serious illness was, for them, quite low). Older people were certainly more cautious that younger ones, leading to much lower infection rates in older cohorts. Some of the government's response to the second wave therefore appeared a little 'over the top' - although only time will tell if this criticism is justified.

There are some very useful ‘top tips’ for incident management at Annex A below.

4. Then Organise …

One person should be given clear, full-time cross-Whitehall responsibility for leading the response to the crisis. That person should confine him/herself to taking strategic decisions. Other responsibilities should be clearly allocated. Tactical decision making should be left to those on the ground.

Individually, you are always secondary to the role you play. If you have a role to play then it's important you play that role. If you don't have a role to play, it's really important you don't get under the feet of people who do.

- Examples:

- It was never clear who was responsible for leading the response to COVID-19.

- That person could have been the Health Secretary but probably should have been the Prime Minister (or possibly Michael Gove, Cabinet Office Minister) in view of the understandable tensions between those most worried about deaths and the impact on the NHS, and those worried about the impact on the economy.

- Complaints that too many decisions were being taken in London, and insufficient use was being made of local throaty knowledge and expertise, appeared to have some force.

5. … and Consult

Continue consulting, intensively, as you develop your strategies in response to the crisis. Again, consultation need not be time consuming, but it should include all those who seem to have interesting things to say, and all those who might reasonably wish to be consulted. This will greatly increase the chances that your strategies will be effective – and accepted by consultees, even if they had argued against them. Modern communications, including social media, will allow you to summarise issues, suggest ways forward, and seek comments, against very tight timetables.

Examples:

- The Chief Medical Adviser said on March 12 – at his and the Prime Minister’s first press conference – that “we are maybe four weeks or so behind Italy in terms of the scale of the outbreak”. But lots of people, including some scientists who were helping to advise the government, correctly argued at the time that the UK was in fact only around two weeks behind Italy. This advice was either not clearly passed on to Ministers, or was ignored by them. This serious mistake undoubtedly meant that the UK went into lockdown far too late, and many lost their lives as a result.

- The teachers unions were not properly consulted before the initial announcement that schools were to be reopened for certain age groups.

- The September 2020 Covid Marshalls consultation document was issued at 1430 one afternoon with responses required by a ridiculously tight 1030 next day.

Be sceptical about early research findings.

- Hurried, poorly designed, underpowered studies can be worse than not doing anything at all.

- An information vacuum and public/media concern encourage a flood of low quality information.

- Research groups that have higher standards, are more careful, better understand the issues, etc. will produce fewer papers or don't engage at all.

Try to identify and allow for unintended consequences.

Measures that might be seem attractive so as to ensure public safety/security do not necessarily have priority over consequences including damage to human rights … nor do they always trump economic damage. Ministers – and if necessary Parliament – need to make these judgments and agree the necessary compromises.

- Non-COVID example: The US emergency response to 9/11 led to all borders being closed. This severely damaged companies operating supply chains over the Canadian border.

6. This is Not Politics as Normal

The public have a sort of unwritten psychological contract with those in power. We expect that the police will treat us with respect. We expect that the government will ensure access to impartial justice. And we expect governments to tell us the truth, set politics aside and do everything in their power to protect us when crises occur. Much follows from this:-

Don’t promise, unless you are near certain to be able to deliver. And try to avoid announcing ‘targets’.

- Targets are, by definition, often missed. They initially reassure the public that concrete steps are being taken. But they focus media attention and destroy confidence if they are not met.

- And targets rarely yield the most effective use of resource within government. They can galvanise officials. But they can lead to excessive resource being needed at the expense of other important areas.

Instead, explain what you are doing, and the extent to which you depend on others, and on technology being made to work.

As noted above, it helps a lot if the government has established itself as generally trustworthy.

A blog about the psychological contract (by Gill Kernick and me) may be found here.

Examples:

- There were numerous missed targets for the introduction of effective testing and contact tracing systems, not least the ‘world-beating test track & trace system’ promised for 1 June.

- Credit for ‘world-beating’ solutions would be better claimed if and when the solutions worked.

- School reopening was announced without it being clear how all children could be kept 1 or 2 metres apart without acquiring extra classroom space and extra teachers.

- Relaxed lockdown rules often seemed illogical, or at least poorly explained. Why could we meet only one parent at a time? Was it realistic to allow lovers to meet as long as they stayed 1 metre apart?!

- Ventilator manufacture:- Let’s invite every manufacturer to bid to build ventilators! How hard can it be to build them? Answer –Ministers were told, but apparently did not hear, that it is very hard to manufacture ventilators that are safe for patients to use. It is extremely difficult to build a controllable machine that will reliably – and over several weeks – deliver exactly the right mixture and pressure of gases to the damaged lungs of a very sick person.

- The Prime Minister announced 'Operation Moonshot' in September 2020:- a £100bn mass testing program depending on unproven technologies and yet-to-be-developed logistics. It would supposedly 'utilise the full range of testing approaches and technologies to help reduce the R rate, keep the economy open and enable a return to normal life.' - all to be in place by 'early 2021'. The announcement was met with understandable incredulity and derision.

Be agile. Learn. Don’t Blame. Admit errors, but make it clear that lessons have been learned. You won’t convince everyone, and your political opponents will criticise your ‘U-turns’, but most of the public will credit you for identifying things that are going wrong, and addressing them.

Examples:

- Minsters did not respond confidently and effectively to concerns about:

- Shortages of PPE

- Deaths in Care Homes

- Higher mortality rates amongst the BAME population

- It was particularly foolish of Jacob Rees Mogg to dismiss parents' and others' concerns about insufficient test capacity as 'carping'.

Lead by Example. Ministers and senior officials must comply with their own legislation, and follow their own guidelines, or else they will lose moral authority, and will encourage others to ignore the same rules.

Examples:

- The Prime Minister, in the early days, seemed disinclined to follow his own social distancing and other guidance. (But he caught COVID-19 which – ironically – probably did much to encourage the rest of us to be more careful.)

- The Prime Minister's later journey across London to exercise in the Olympic Park appeared to contravene his own government's guidance. He should have apologised for what may have been a minor breach, or explained why it was permissible.

- Dominic Cummings’ trip to Durham and (the PM's father) Stanley Johnson’s trip to Greece will have damaged the public’s faith in the Government, particularly because Ministers refused to accept that guidance had been breached.

- Health Secretary Matt Hancock's clinch with his mistress Gina Coladangelo (and Dept of Health Non-Exec Director) similarly suggested that there was 'one rule for them, another rule for the rest of us'.

Provide Accurate Information. Once reliable information becomes available it should be published in a form that allows it to be easily understood. It should not be presented in a way that appears particularly favourable to the Government.

Examples:-

- It should not have been possible for the Head of the UK’s Statistics Authority to write to the Health Secretary about COVID testing data in these terms: "I warmly welcome of course your support for the Code Of Practice for Statistics but the testing statistics still fall well short of its expectations. It is not surprising that, given their inadequacy, data for testing are so widely criticised and often mistrusted."

- The Prime Minister and Education Secretary's August assurance that 'a study' showed that it would be safe for children to return to school should have been accompanied by publication of that study. Instead, there were media reports next day that the data in the study had not been fully analysed, and that its tentative conclusions had been over-hyped.

Avoid gimmicks and jokey language. The public are unlikely to be in the mood to be entertained.

Examples:

- NHS lapel badges are no substitute for plentiful PPE.

- “Whack-a-mole” is by definition a game which the moles win. It’s not a good analogy for an anti-virus strategy.

- Marina Hyde was not far wrong when she commented that

- "The government’s crisis communications strategy could not be going worse if it was being led by the last speaker of a dead language .... People are still clearly extremely confused by what the advice is. Never have bullet points been more called for, and you’d think someone as obsessed with the second world war as Johnson is would know that an effective Ministry of Information was inextricably linked to the success of the war effort. Unfortunately, as indicated, Johnson is basically just a columnist. ... How to put this in terms that even a wildly overeducated prime minister can understand? JUST TELL US THE INFORMATION. It’s a public safety briefing, not a fricking ring quest. The government’s inability to clearly define essential terms means we are in a situation where “self-isolating” demonstrably means a range of things to different people. Same with “social distancing”. These urgently need simple and precise definition, and a comms blitz everywhere from social media to news bulletins to short TV ads. Instead, Johnson prefers to chuck new soundbites on the pile. The current one is the pledge that “we can turn the tide within the next 12 weeks”. If you missed this clip, don’t worry. My suspicion is that you’ll be seeing it hundreds of times more this year. It has a strong “Over by Christmas” vibe to it, and is the sort of thing you could imagine on the side of a bus.

In short - Trust in government is a vital and precious resource. Do not squander it!

7. Communications

Identify – ideally only one person – who will take responsibility for telling the public what is happening.

In general, it is probably best if the spokesperson is not a minister, given public distrust of politicians, and given the possibility that they will not listen to communications advice. Also, they will attract political questions which will impede clear communication of important messaging.

An (otherwise not well known) expert is often best, such as the Chief Veterinary or Medical Officer.

- They should aim to demonstrate calmness, confidence, trustworthiness and competence.

- They should remember that 90% of the information initially reaching the crisis management team will be wrong, so they should not go into detail. (But see above for the need for honesty and accuracy once reliable data becomes available.)

- Once reliable facts are available, they should focus on communicating that information. (Click here to read excellent advice from Alastair Campbell.)

Examples:

- Politicians fronting the daily COVID press conferences have frequently been so worried about ‘Gotcha!’ questions that they have been unable to give sensible answers to straight questions. They have also felt it necessary to offer promises which cannot be kept, this diminishing trust in the government’s ability to cope with the crisis.

- No.10 briefed the press that "booking holidays is a choice for individuals" on the same day that the Transport Secretary said that "people shouldn't be booking holidays now".

- Pre-COVID – During a fuel supply crisis, a senior politician encouraged the public to hoard petrol in jerry cans kept in garages … forgetting that hoarding should never be encouraged, not everyone has a garage, and petrol is highly flammable.

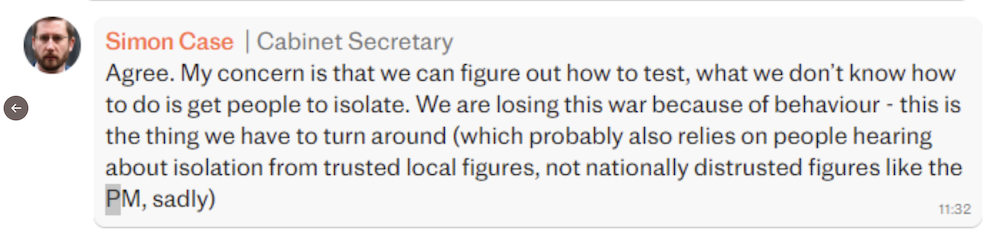

- Some years later, a leak of his WhatsApp messages showed that the Cabinet Secretary was familiar with the above advice:-

Ensure that your decisions, regulations and guidance can be easily communicated. If not, there may be a problem with the policies. In particular, guidance must be consistent with legislation.

Examples:

- ‘Plain English’ guidance – a bit like the Highway Code – would have been very helpful in summarising lockdown guidance as it develops.

- Apart from everything else, it would have had to reconcile the contradictions in government policy.

- The preparation of such guidance would most likely have exposed some of the apparent illogicalities and/or impracticalities in the developing guidance.

- Many lockdown relaxation decisions were pre-briefed to the media, in general terms only, sometimes many days before they were due to take effect. This encouraged many to apply the new rules (illegally) before they came into force. And the lack of detail caused misunderstandings and some confusion.

- The ‘air bridges’ unattributable pre-briefing was classic. The Times reported that “travel sites were inundated with demand for [overseas] summer breaks” … until … Home Secretary Priti Patel warned that “these measures won’t come into force overnight … there will be an announcement in the next few days … [the public should wait and] listen to the advice”.

- Once air bridges had been introduced, travelers were not warned that quarantine-on-return might be introduced at very short notice – as happened only two weeks later once many thousands of Brits had begun their summer holidays in that country.

- Subsequent government briefing seemed oblivious of the fact that an employee who had less than two years service, and who self-isolated on return from Spain, could be sacked by their employer without being able to complain of unfair dismissal.

- The local lockdown strategy was described as “whack-a-mole”, but no one could tell from this who was supposed to do the whacking, or what sort of mallet to use. It would have been better to explain quite clearly what would trigger local lockdowns, and which powers sit centrally and which locally.

- The announcement of new lockdown rules for Greater Manchester was announced in a tweet at 2116 one evening - so giving less than three hours notice. This was hardly likely to improve trust in HMG's apparently panicky handling of this issue, and seemed to many to be grossly unfair, not least to those planning Eid celebrations next day. It was for the Islamic community the equivalent of Christmas lunch and associated festivities - including church services - being prohibited in an announcement at 2116 on Christmas Eve.

But do not simplify complex messages for specialist audiences. Encourage and trust intermediaries to communicate as necessary to their readers and members.

Although you will wish to make full use of social media, the broadcast and print media are an important intermediary in communicating with the public in times of emergency. They need to be assisted and respected.

Do not unveil longer term strategies without significant detail being in place. You must be able to answer obvious questions.

Examples:-

- Quarantine policy was confused:- Initially no quarantine, then quarantine for everyone, then ‘air bridges’, then a ‘traffic light’ system, then … silence!

- Testing and ‘test & trace’ were sometimes briefed as absolutely vital, and sometimes as unimportant.

- The Joint Biosecurity Centre was announced as having a key role in setting the COVID alert level, which would in turn inform lockdown/relaxation policy. Many weeks later, and well after significant relaxation decisions had been taken (and after a renewed lockdown in Leicester) the centre had still not formally come into existence.

Prepare to be blamed. The over-adversarial nature of UK politics cannot be totally wished away, so it should be handled as a formal risk to your plans – a risk that should be mitigated in an open way.

Do not promise regular press conferences. The absence of worthwhile announcements soon leads to excessive spin, empty promises, repackaged repetitive statements, and consequential lack of trust – plus wasted official and Ministerial time.

- Example: It was a mistake to promise daily press conferences during the COVID-19 crisis.

See Annex B below for communications advice contained in the conclusions of the BSE Inquiry.

Further Reading

The IfG published its initial 'lessons learned' [from Covid] report in August 2020:- Decision Making in a Crisis.

It followed it up with Responding to Shocks - 10 lessons for government in March 2021

It also published Science Advice in a Crisis.

Tim Harford has written a very interesting blog explaining Why we fail to prepare for disasters.

More detailed advice on handling risks to health and safety, including communications advice, may be found here.

Annex A

Here are some very sensible Top Tips for Incident Management from Sir James Bevan, Chief Executive of the Environment Agency:-

Lead: if you are your organisation’s leader, you need to lead the response to a big incident. Don’t try and do the day job as well. The incident is the day job till it’s over. Be decisive: be prepared to take big decisions. In an incident the biggest risk is not taking a decision at all, or taking it too late. You will not have all the facts: decide anyway.

Move fast: Flick the switch early to put your organisation into incident mode. If you don’t get ahead of the curve you will never catch up. So over-resource at the start: people, kit, whatever. You can always scale back later. Establish your battle rhythm immediately – which meetings when with whom to do what – and clear roles and responsibilities.

Get on the ground: The absent are always wrong. Being present and visible at the scene of an incident is as important as what you do when you get there. So get yourself and your team to the scene as soon as possible.

Have a strategy: Be clear what your goals are and ensure everyone in your team knows. Be ready to adjust your strategy as the situation changes, because it will.

Win the air war: The media battle (the air war) is as much a part of the incident as your operational response (the ground war). You need to win both. So use the media: don’t shy away from it. Have a simple message and keep on saying it. Get the tone right: calm, authoritative, empathetic, commitment to do what’s needed. Accept the inevitability of critical reporting: it’s not personal. It will go away.

Manage upwards: We all have bosses. Tell them what you are doing and listen to what they want.

Stay well: Look after your staff’s wellbeing and your own. Ensure everyone is fed and watered and gets a break, including you. Tired people make bad decisions.

Be ready beforehand: Have an incident plan and practice beforehand. No plan will survive contact with reality, but it’s better than not having one. Time spent in preparation is never wasted: what you do in peacetime is reflected in how you perform during the incident.

Learn the lessons afterwards: It will never be perfect. But each time you do something right or wrong, you will learn valuable lessons for next time. Do a wash up afterwards, write down the main lessons and keep them handy. You will need them again.

Annex B

Here is an extract from the conclusions of the BSE Inquiry:

- To establish credibility it is necessary to generate trust

- Trust can only be generated by openness

- Openness requires recognition of uncertainty, where it exists

- The public should be trusted to respond rationally to openness

- Scientific investigation of risk should be open and transparent

- The advice and reasoning of advisory committees should be made public

- The trust that the public has in the Chief Medical Officer is precious and should not be put at risk

- Any advice given by a CMO or advisory committee should be, and be seen to be, objective and independent of government.